The Illusions of Empire

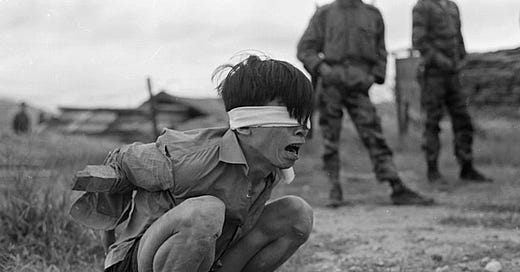

The Quiet American (2002), directed by Phillip Noyce, is a deeply pensive film that unfolds against the backdrop of a Vietnam teetering on the edge of revolution. Europeans and Americans exploit both the people and the land, oblivious to the signs of an impending civic breakdown. The film centers around Thomas Fowler (Michael Caine), a seasoned British journalist covering the First Indochina War between Vietnamese nationalists and French colonists. Fowler’s relationship with Phuong (Do Thi Hai Yen) is steeped in self-interest—he clings to her as a source of comfort, feeding her empty promises of marriage, a personal microcosm of how Vietnam itself is used and discarded by the Western world. Together, they spend their nights dancing in lounges and smoking opium.

Enter Alden Pyle (Brendan Fraser), a seemingly mild-mannered American on an aid mission. Pyle quickly falls for Phuong, setting up a rivalry between himself and Fowler—a battle of Western masculinity unfolding in a country on the brink of collapse.

Honestly, this the most cringeworthy aspect of this film.

But this love triangle, awkward and trivial in contrast to the war’s true stakes, ultimately serves as a prelude to a far more dangerous conflict: the ideological battle between an old-world journalist who has seen too much and a fresh-faced American convinced he can remake Vietnam in his own image.

Mission Impossible

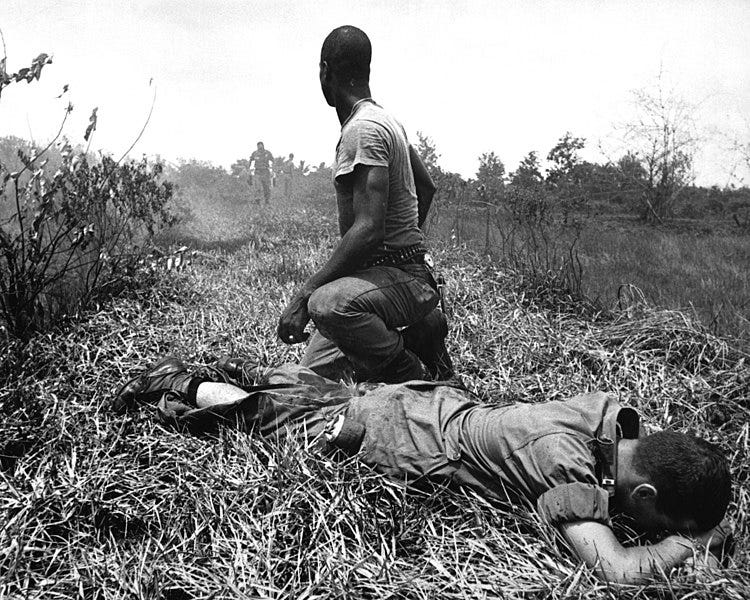

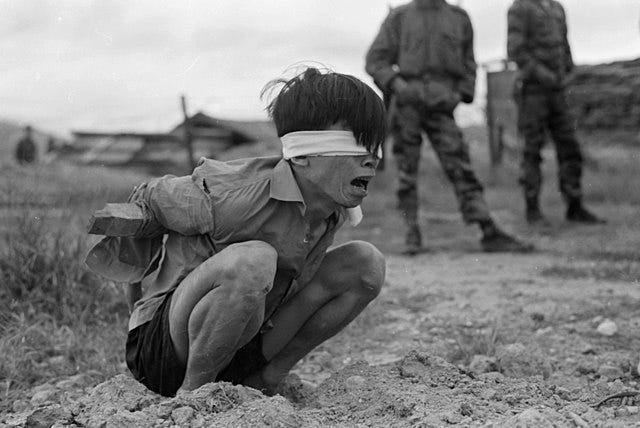

Fowler, ever the investigative journalist, grows suspicious of Pyle’s so-called aid mission and visits his makeshift site himself. What he discovers is chilling—diolacton, a chemical precursor used to manufacture explosives. This revelation confirms Fowler’s suspicions that Pyle is secretly supplying materials for a covert paramilitary force in Vietnam. Pyle, a man convinced that America must intervene to create a "third force,” a nationalist alternative to both French colonialists and communist insurgents, has unwittingly engineered catastrophe. His well-intentioned but naive idealism manifests in devastating bombings in Saigon, killing innocent civilians in the name of an abstract ideological struggle.

Fowler’s discovery forces him to confront Pyle’s deception and, more broadly, the consequences of U.S. interventionism—how America’s idealistic hubris, when untethered from local realities, often sows chaos rather than stability. Pyle is not the passive do-gooder he projects himself to be; he is an active player in the machinery of empire, believing the loss of innocent lives is a necessary trade-off for "progress."

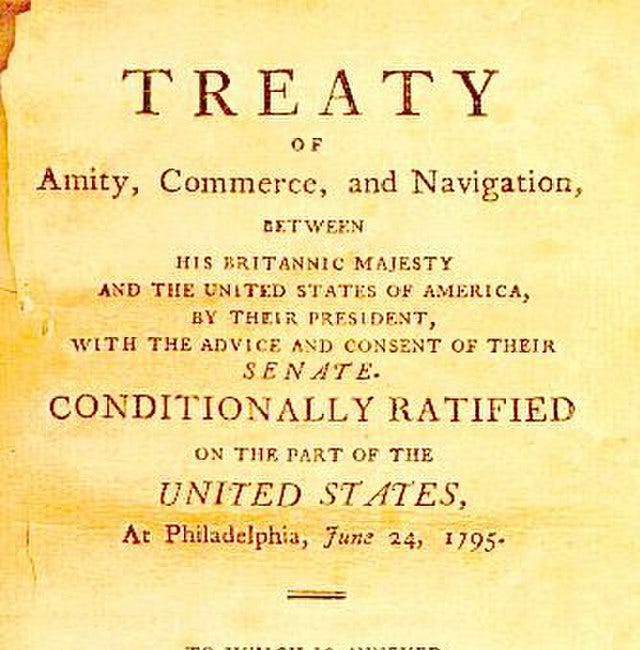

Pyle’s actions mirror real-world historical patterns of American covert operations during the Cold War, particularly the CIA-backed interventions in Guatemala (1954), Iran (1953), and Nicaragua (1980s). In these cases, U.S. operatives, convinced they were fostering democracy, instead destabilized governments and inflicted long-term harm.

Two years ago yesterday, I wrote about the long shadow of the Vietnam War:

The Vietnam War Era (1949 - 1983)

The 2010s - The Vietnam Veterans Memorial at Washington, D.C. at night. The Vietnam Veterans Memorial honors over 58,000 who died in service in the Vietnam War, and those who are still missing in action. The names are listed chronologically on the wall.

This week, I have been writing about the nuances of American foreign policy in a time of growing isolationism. Check it out:

Monday Thought: Pax Americana

“What the people want is very simple. They want an America as good as its promise.”

A Poetic Omen

The film’s themes explode to the surface when Fowler confronts Pyle over the realities of his actions. Fowler warns him of the destruction the "third force" will unleash. Pyle, brimming with confidence, dismisses the concerns outright:

"The French aren’t going to stop the communists. They don’t got the brains, they don’t got the guts!"

Fowler’s response is measured yet damning. Instead of arguing further, he simply recites lines from Arthur Hugh Clough’s Dipsychus:

"I drive through the streets, and I care not a damn;

The people they stare, and they ask who I am;

And if I should chance to run over a cad,

I can pay for the damage if ever so bad.

So pleasant it is to have money, heigh-ho!

So pleasant it is to have money."

Pyle interrupts before Fowler can finish, jumping in on the last line: "I can pay for the damage." The exchange is telling because Pyle, without realizing it, embodies the very arrogance Fowler is condemning. In its satirical tone, the poem captures the recklessness of wealth and power—how those with privilege can cause harm and believe they can simply "pay for the damage." Fowler, the seasoned British journalist and a man who has seen the costs of empire firsthand, watches in dismay as Pyle, the loud American, recites the words unironically, oblivious to the warning within them and resembling a young nation still resolving its internal hypocrisies but given the keys to the global system of power.

I’m Glad I Didn’t Live in the 50s

The Quiet American (2002) stays true to Graham Greene’s novel, which sharply critiques Western intervention. In contrast, the 1958 adaptation rewrites the narrative into Cold War propaganda, removing much of the novel’s moral ambiguity. That version paints Pyle as an unambiguous hero, aligning with America’s anti-communist messaging at the time. By restoring Greene’s original themes, Noyce’s 2002 adaptation provides a searing indictment of interventionist hubris and its devastating consequences.

Pax Americana Reimagined

Watching The Quiet American, it is impossible not to reflect on the illusions many Americans live under—illusions that have allowed our foreign policy to repeat its blind spots for generations. As America shifts toward isolationism in a multipolar world, policymakers and commentators must reckon with how the country arrived at this moment. The disillusionment in the wake of Pax Americana’s decline is not simply about the failures of military interventions—it is also about our narrow conception of nationalism in other countries, our reliance on bravado over understanding, and the scars of internal hypocrisy that we export to the rest of the world.

For those still reeling from the hangover of American exceptionalism, The Quiet American is a sobering film. Fowler realizes the truth about Pyle not when he hears his words but when he sees him speaking fluent Vietnamese after a catastrophic explosion. The illusion of the benevolent American crumbles—Pyle is not the wholesome do-gooder he markets himself as, but an active participant in destruction.

As America grapples with its shifting global role, we must ask:

Will we learn from our past?

Or will we, like Pyle, cling to illusions until the damage is beyond repair?