“What the people want is very simple. They want an America as good as its promise.”

- Barbara Jordan

Commentators often argue that Americans are turning inward because they are ignorant, too self-involved, or distracted to understand the importance of U.S. power abroad. But that argument misses the mark. Disillusionment, not ignorance, is driving the retreat from global engagement. The Black American experience uniquely depicts the tension between American idealism and imperialism.

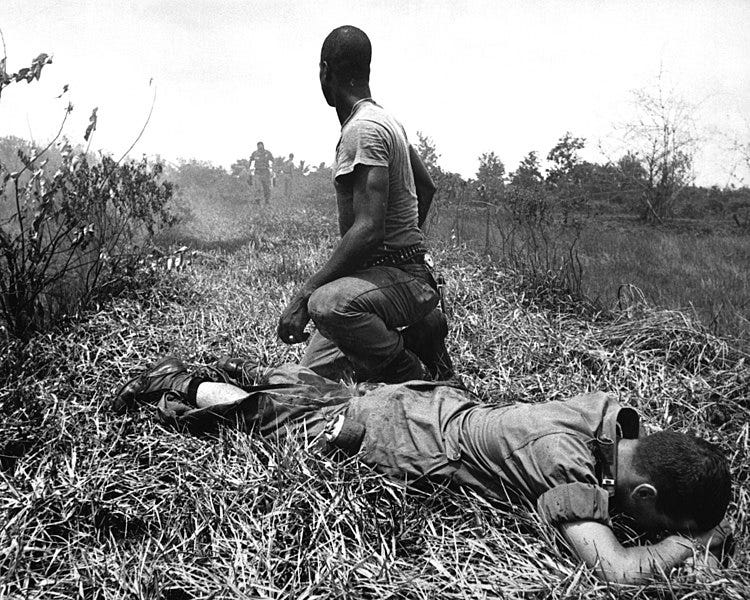

For generations, Black Americans have served and sacrificed on the world stage for a nation that had a complex, often unfulfilling, relationship with democracy at home. Their skepticism of U.S. leadership abroad wasn’t necessarily ill-informed isolationism as it was lived wisdom.

The Imperial Paradox

History teaches us that Black Americans often experience America’s systemic failures at exponentially higher degrees than other Americans. From the foxhole to their front doorstep, they’ve been asked to believe in promises that never included them. Black soldiers fought in every American war, from our earliest conflicts to the Buffalo Soldiers to the Tuskegee Airmen. They fought for ideals that, upon returning home, they were denied. The betrayal was a lesson about the hierarchy, the marketing techniques of modern nation-states, and the true motivations guiding American foreign policy.

Long before the mainstream turned against Vietnam, Black activists were condemning the war not out of anti-Americanism but from a deep understanding of American hypocrisy as the Black community disproportionately sent its youth to fight in the war’s earliest years.

Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. called the Vietnam War “a symptom of a far deeper malady within the American spirit,” and he was right. In his speech “Beyond Vietnam,” King argued that the war was poisoning a rare opportunity for America to fulfill its professed ambition to enshrine economic and social democracy. He warned that the war drained resources from the War on Poverty and undermined efforts to create a just and equitable society at home.

"A nation that continues year after year to spend more money on military defense than on programs of social uplift is approaching spiritual death."

— Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., Beyond Vietnam (1967)

One can look further back in history than the Vietnam War era to find African Americans questioning foreign policy actions with so much left unresolved in our borders. During the Spanish and Philippine-American Wars, the Indianapolis Freeman, the first illustrated Black newspaper in America, published an editorial outlining the newspaper’s position, stating:

The U.S. recruiting officer is expected in Hartford this week to receive names of men for the prospective Spanish-American war. Great excitement prevails here among all classes, and some of our colored men seem enthusiastic over the idea of enlisting in defense of the government, while some are more reserved and common-sensed, asserting that no colored man should never again offer his services to protect a government that does not protect him. The government of the United States will allow some of her most loyal and true citizens to be burned and shot to pieces, like dogs, without protection, and go right on ignoring their rights and claims as if all were peace and happiness in the family; and yet, when a foreign war is threatened, these same ill-treated citizens are wont to be rushed to the front in the name of protecting the nation’s honor. Such injustice is not tolerated by any other civilized nation; not even is Spain guilty of such discrimination among her own citizens. As a race what means have we for checking such unjust discrimination? Colored men of Hartford, let us think before acting. If the government wants our support and services, let us demand and get a guarantee for our safety and protection at home. We want to put a stop to lynch law, the butchering of our people like hogs, burning our houses, shooting our wives and children and raping our daughters and mothers. In short, as a race, we want indemnity for the loss of ten thousand Negroes who have been lynched and butchered and slaughtered since the civil war. When we are guaranteed freedom and equality before the law, as other American citizens, then we will have a right, as such, to take up arms in defense of our country.

-Indianapolis Freeman, March 19, 1898

Imperialism for many Black Americans was a paradox that proclaimed democracy and progress on the surface and abroad but further enshrined antidemocratic incentive structures at home.

Disillusionment Now

Today, the disillusionment that Black America has carried for generations. Black Americans generally prioritize economic well-being over foreign policy when considering political candidates. This doesn’t mean they do not understand how international developments and domestic economics connect. It is mainly a trend suggesting Black Americans, like most Americans, are concerned with the here and now. The Carnegie Endowment for International Peace survey showed that Black Americans don’t prioritize foreign policy but still pay attention to developments. It found educational attainment and income correlated with concern for foreign policy:

“Highly educated respondents and those reporting an annual household income of $100,000 or more were more likely to see a candidate’s foreign policy agenda as important. (Studies have shown that higher educational attainment is strongly correlated with higher earnings, partially explaining why these two demographics trend closely together.) In terms of education, six out of ten respondents (59 percent) with a postgraduate degree reported that a candidate’s foreign policy agenda is “very important.” For all education levels, most respondents felt that a candidate’s foreign policy is relatively important, but those with a high school diploma or less and those with some college education were more likely to say that a candidate’s foreign policy agenda is not important, at 18 percent and 21 percent, respectively”

The lack of traditional education does not necessarily signify that these Americans don’t understand the benefits of U.S. power. It’s because they know exactly where those benefits have gone—and where they haven’t. The same poll concludes that:

“It is interesting to note that the number of individuals who reported familiarity with foreign policy issues (72 percent) sits roughly 11 percentage points lower than the number of those who reported that foreign policy mattered to them when they vote for a presidential candidate (83 percent). This finding tracks with a 2019 poll by the Council on Foreign Relations, which revealed that Americans lack knowledge of world affairs yet consider such issues to be relevant to their lives. Again, this phenomenon could partially be explained by the fact that although Americans may not be well versed on such issues, they have a rudimentary understanding that these issues impact their lives and at least hope that the candidates they vest trust in will carry out a foreign policy agenda that benefits them.”

Black Americans, like other Americans, have seen trillions spent on forever wars while their communities crumbled. They’ve watched military contractors get rich while their hospitals closed. They know that “U.S. leadership” has meant power for the powerful and sacrifice for everyone else.

Maybe the Failure Was Leadership, Not the Public?

What’s breaking isn’t the public’s understanding of U.S. power but their faith in its use. Americans aren’t tired of engagement; they’re tired of wars fought for elites and promises broken for everyone else.

The forever wars in Iraq and Afghanistan burned through over $8 trillion yet left the Middle East in utter chaos and increased the chances of proliferated extremism. Meanwhile, back in the U.S., schools remain underfunded, infrastructure is neglected, and public health is gutted. This wasn’t an accident—it was a choice.

This is a pattern Black Americans know well. After World War II, the GI Bill created the modern middle class—but not for everyone. Black veterans were systematically denied those benefits through redlining, segregation, and discrimination. The promise of American power abroad once again ended at the color line. Today, working-class Americans of all races are confronting a similar truth: U.S. global leadership's so-called “benefits” rarely reach their doors.

The Reagan Legacy: Optimism With Blind Spots

To understand today’s disillusionment, we must come to terms with the permission structure that made it possible. No U.S. president sold the idea of Pax Americana with more optimism than Ronald Reagan. He made Americans believe in the moral power of U.S. leadership abroad. But his optimism had a fatal blind spot: it was an optimism determined to sanitize and cover up the experiences of marginalized groups.

Reagan’s “Morning in America” was always about selective sunlight. It celebrated prosperity for those already inside the American dream while those on the margins lived through a different reality. His vision of global power sanitized, sidelined and ignored Black experiences—both at home and abroad.

When Black Americans demanded that Reagan confront apartheid in South Africa, he chose “constructive engagement,” a policy that prioritized stability over justice. Black leaders, like Coretta Scott King, condemned sanctions on the apartheid regime and urged U.S. Congress to “explore other avenues of nonviolent action that would not be as damaging or last as long as sanctions.” Adding to her critiques, she urged the Reagan administration to consider divestment when she traveled to South Africa.

At home, the contradictions of Reagan’s Pax Americana only deepened. His soaring defense spending fueled deficits that were later weaponized to justify cutting the very social programs that communities of color relied on. Meanwhile, the Reagan administration waged a moralistic and punitive war on drug use—eschewing investments in rehabilitation or mental health care in favor of criminalizing drug users, a strategy that played on stereotypes about African Americans rather than addressing root causes.

This policy culture extended to the militarization of American streets and police forces, which devastated Black communities and turned neighborhoods into war zones. Simultaneously, the administration’s foreign policy faced scrutiny amid the Iran-Contra scandal, as investigations probed whether U.S. covert operations in Nicaragua were funded in part through drug trafficking—an allegation that, despite official denials, has lingered in the grey zone of America’s collective cynicism and distrust.

Reagan’s version of global leadership wasn’t just a Cold War strategy—it was a worldview that said American strength mattered abroad but not justice at home. And that contradiction laid the groundwork for today’s disillusionment.

What Happens When Power Serves Justice, Not Empire?

Pax Americana wasn’t always a failure.

When U.S. power aligned with justice—it lifted rather than imposed, thus bringing real progress. Some of America’s greatest global initiatives came not from dominance but from partnership, purpose, and empathy:

PEPFAR (2003): Saved 25 million lives in Africa’s fight against HIV/AIDS.

Millennium Challenge Corporation (2004): Invested $15 billion in sustainable development across Africa.

African Growth and Opportunity Act (2000): Boosted African exports to $6.7 billion annually.

Feed the Future (2010): Lifted 23 million people from poverty through agricultural programs.

COVAX (2021): Delivered 1.2 billion COVID-19 vaccine doses globally.

These successes weren’t about projecting hard power. It was about spreading influence through magnanimity under the umbrella of America’s disproportionate power and wealth. They succeeded because they prioritized partnership over paternalism.

The Collapse of Pax Americana: A Reckoning, Not a Retreat

The disillusionment we see today is not a rejection of America’s role in the world—it’s a demand for America to align its role with its values. Americans aren’t saying, “Do less.” They’re saying, “Do better.”

Black Americans have lived both sides of the U.S. story—the promise and the betrayal. Their disillusionment is a warning: When power serves the few, it breeds mistrust and decay. But when power serves justice, it creates trust, stability, and pride.

Reclaiming the Promise of American Power

Barbara Jordan’s words still echo: “What the people want is very simple. They want an America as good as its promise.”

The end of Pax Americana does not have to be the end of American leadership.

The path forward is clear:

Power without justice creates disillusionment.

Power in service of justice redeems America’s promise.

Through analyzing the experiences of Black Americans, people who have lived through the contradiction of America’s ideals and actions, the larger public is offered a warning and a guide. They are not calling for retreat when they say America has broken its promises. They are demanding that America finally become the nation it claims to be. The Carnegie Endowment for International Peace conducted more research on Black American views on foreign policy, but this time, it focused on how race relations shaped them. The conclusion was clear:

“In 1966, citing the death of Sammy Younge, Jr., a Black military veteran killed in Alabama for protesting segregation, the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), an African American student organization, publicly lambasted the Vietnam War effort. The group found it difficult to support U.S. efforts to promote democracy in Southeast Asia when the promises of equality were denied to many African Americans.

SNCC leadership filtered support for U.S. foreign policy initiatives through the lens of racial well-being, as just one instance in a long tradition of African American thought. Similar to activists of previous generations, the leaders wrestled with whether or not to support U.S. efforts to preserve democracy abroad while economic, political, and social inequalities existed along racial lines at home.

History may not repeat itself, but it does rhyme. As racial issues persist, such as vigilante violence, economic inequality, and the rollback of legislation meant to address historical harm, it is possible that some African Americans today may factor these issues into their calculations of whether to support certain U.S. foreign policies.

The data presented in this article detail how, for many, domestic politics do not stop at the water’s edge. There is a relationship between domestic politics, specifically racial equality, and how African Americans think about the role the United States should play in various global initiatives.

African Americans are not against the United States taking a global leadership role, but many want the role to be different from the past and to prioritize a different set of issues. To many African Americans, the U.S. role in the world should not lead to armed conflict and should not treat a unipolar or bipolar world order as the default. As the White House attempts to rationalize some of its most pressing policies, such as tension with China and Russia, to the American people, it will help to bear this in mind.”

And if history teaches us anything, it’s this: When Black America speaks, it’s not just for themselves—it’s for what comes next.