Commerce, Power, and the Jeffersonian Fantasy

Over the past two weeks, we’ve stepped away from presidential politics to examine the world of early Black Americans—figures like Phillis Wheatley, who challenged the era’s contradictions, and the Lilburn brothers, whose brutality exposed the myth of the Southern gentleman. But now, we return to the halls of power, where another myth was taking shape—the Jeffersonian fantasy that commerce, rather than military strength or political pragmatism, could shape a just and peaceful world.

Historian Gordon S. Wood captures the way revolutionary fervor informed foreign policy idealism in the early Republic in his book Empire of Liberty:

“Just as liberal Americans in 1776 had sought a new kind of domestic politics that would end tyranny, so too had they sought a new kind of international politics that would promote peace among nations and, indeed, might even see an end to war itself. The American Revolution had been centrally concerned with power—not only power within a government but power among governments in their international relations. Throughout the eighteenth century liberal intellectuals had looked forward to a newly enlightened world in which corrupt monarchical diplomacy, secret alliances, dynastic rivalries, and balances of power would be eliminated. In short, they had hoped for nothing less than the abolition of war and the beginning of a new era of peaceful relations among nations.”

“Monarchy and war were thought to be intimately related. Indeed, as young Benjamin Lincoln Jr. declared, ‘Kings owe their origin to war.’ The internal needs of monarchies—the requirements of their bloated bureaucracies, their standing armies, their marriage alliances, their restless dynastic ambitions—lay behind the prevalence of war. Eliminate monarchy and all its accouterments, many Americans believed, and war itself would be eliminated. A world of republican states would encourage a new, peace-loving diplomacy—one based on the natural concert of the commercial interests of the people of the various nations. If the world’s people were left alone to exchange goods freely among themselves—without the corrupting interference of selfish monarchical courts, irrational dynastic rivalries, and the secret double-dealing diplomacy of the past—then it was hoped, international politics would become republicanized, pacified, and ruled by commerce alone. Old-fashioned diplomats might no longer be necessary. This was the enlightened dream of liberals everywhere, from Thomas Jefferson to Immanuel Kant.”

“Suddenly, in 1776, with the United States isolated and outside the European mercantile empires, Americans had both the opportunity and a need to put into practice these liberal ideas about international relations and the free exchange of goods. Thus, commercial interest and revolutionary idealism blended to form a basis for American thinking about foreign affairs that has lasted even to the present.”

Back in the 90s

But as America entered the 1790s, the idealistic dream of commerce-driven peace ran into hard reality: the young republic was surrounded by European empires, all of whom saw it as a potential pawn or rival. The Spanish projected power in Florida, Louisiana, and the Caribbean. The British controlled forts in the Midwest despite the terms of the Treaty of Paris. And having been decisive in American independence, the French still expected U.S. loyalty in return.

The demands of this environment made it nearly impossible to expand without provoking a major power. It’s also hard to poke a bear when you don’t have an adequate stick or hunting rifle to back you up. The America of the 1790s had no strong military and thus relied on commerce as its primary means of influencing global affairs.

Jefferson’s Economic Idealism vs. Hamilton’s Pragmatism

Jefferson, the luxurious idealist, believed that commerce alone could dictate the actions of nations rather than warfare or the petty maneuvering of monarchs. His flashpoint came during his time as Secretary of State when he clashed bitterly with Alexander Hamilton and President Washington over the future of U.S. foreign policy.

He found an ally in James Madison, who had once championed the Constitution but grew skeptical of how Federalists expanded the powers of the central government. Together, Jefferson and Madison developed a theory:

Levy tariffs on Britain, harming its economy.

Trigger a domino effect that would force Britain into economic collapse.

Make the U.S. an independent trading power free from British influence.

Of course, this was wildly implausible because the British economy was too diversified to be crippled by U.S. tariffs. Also, America relied on Britain far more than Britain relied on America—with ¾ of U.S. trade tied to Britain, while only 1/6 of Britain’s economy depended on the U.S.

Hamilton’s Financial System and the Reality of British Trade

To make matters worse for Jefferson’s vision, British trade—despite its naval aggressions—was crucial to Hamilton’s financial program. For one, customs duties on British imports funded the national government. These revenues also paid off war debt, lowered state taxes, and legitimized the Washington administration and the new Constitution.

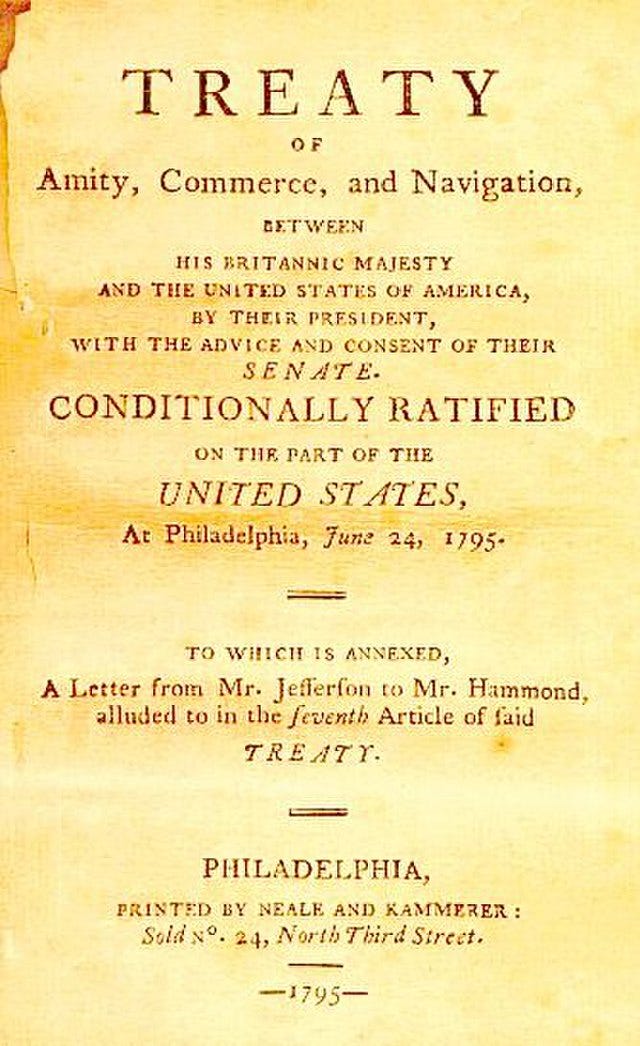

But still, the partisan fires burned over Jay’s Treaty in 1794, as Washington and Hamilton sought to stabilize trade relations in the face of rising tensions between Britain and France.

Jay’s Treaty

John Jay, the first Supreme Court Chief Justice, and a leading Federalist, was sent to Britain to negotiate peace and secure U.S. trade routes. His treaty prevented war but also restricted American trade in ways that enraged Jeffersonians:

Britain could continue seizing U.S. ships trading with France.

U.S. merchants were limited in their access to British Caribbean ports.

No compensation was given for past British seizures of American ships.

While Federalists saw the treaty as a necessary compromise, Jefferson and Madison denounced it as a humiliating surrender, incorrectly believing that trade restrictions could force Britain into better terms.

The Jeffersonian Reaction: Commerce as a Tool of Revolution

This was a letdown for the Jeffersonian Republicans, who saw economic pressure as a weapon of diplomacy. As Thomas Paine, an ideological ally of Jefferson, put it:

“Our plan is commerce, and that well attended to will secure us the peace and friendship of all Europe; because it is the interest of all Europe to have America a free port.”

The administration’s response, however, was rooted in strategic patience as Wood writes, the Federalists wanted to “arm in preparation for war while attempting to negotiate peace.” Hamilton believed America could become a powerful war-making state, but only after decades of industrial and financial growth. But Jefferson and Madison were not patient men in this instance—they wanted to test their free trade doctrine immediately. Besides, what was the point of fighting the Revolutionary War if America remained a client state? And why should Britain dictate American trade after the U.S. had declared its independence? The Jeffersonian bleeding-heart revolutionaries wanted a clean break from Britain—yet at this moment, they lacked the power to enforce their vision.

A Pattern Emerges

Jefferson and Madison’s idealism did not disappear—it would become policy when they assumed the presidency. Their belief that commerce alone could reshape global politics would later result in the disastrous Embargo Act and War of 1812.

A pattern had been set: America’s global footprint would always be shaped by a push and pull between idealism and pragmatism. The lofty dreams of elites living off the spoils of slavery versus the hard calculations of self-made masters of systems—an enduring contradiction that defines American power.