Reader Note: This blog has become one of the fastest-growing history blogs on Substack, recently ranking 21st out of 100 on Substack’s new “Rising” list. I can’t thank you enough for the support—it truly means the world to me. After years of feeling like I was hitting a brick wall and wondering if I should give up writing, your encouragement has made all the difference.

A special thank you to the editors at The Bulwark who have been a consistent and inspiring source of encouragement.

Let’s keep the momentum going!

Cutting Bureaucracy

Thomas Jefferson entered the presidency with a mission to “republicanize” a nation he saw as burdened by sprawling bureaucracy. His election was propelled by a marketing campaign fueled by a growing newspaper presence branding Federalists as elitist and out of touch. Last week, I reflected on this:

Selling Democracy to the Masses (Empire of Liberty #7)

Reader Note: Starting this month, two of my four monthly Monday posts will be available exclusively for paid subscribers. These pieces will be deeply researched and centered on challenging my own priors, with the goal of normalizing intellectual growth, curiosity, and the ongoing work of identifying our blind spots. This space is about engaging with com…

As the new president, Jefferson initiated the first federal cutting spree—a practice that would become a long-term liability. To Jefferson and his Democratic-Republicans (or Jeffersonian Republicans, as they were known then), this was democracy in action. However, that vision of democracy did not include enfranchising people or acknowledging their own claims to aristocracy. Instead, it meant laying the groundwork for democratization, even if its benefits wouldn’t be felt in their time. Jefferson’s concept of democracy, like many American ideals, could be molded to serve different agendas—a truth that remains relevant today. For Jefferson and his successor, James Madison, democracy meant reinforcing states’ power over federal authority.

In his first message to Congress, Jefferson declared that the federal government “was charged with the external and mutual relations only of these states.” The states, he insisted, were the rightful caretakers of “our persons, our property, and our reputation, constituting the great field of human concerns.”

Ironically, as Gordon S. Wood points out in Empire of Liberty, the federal apparatus Jefferson deemed excessive was, by European standards, remarkably small. When Jefferson took office in the still-developing Federal City of Washington, D.C., the War Department consisted of only a secretary, an accountant, fourteen clerks, and two messengers. The Secretary of State had a chief clerk, six clerks (one running the patent office), and a messenger. The Attorney General didn’t even have a clerk. Yet, Jefferson saw this tiny federal bureaucracy as “too complicated, too expensive,” with offices that had “multiplied unnecessarily.”

Jefferson’s zeal for “republicanizing” extended to dismantling the modest navy and army established by the Federalist program. He removed Federalist officers from the military and installed new ones loyal to his administration. His disdain for standing armies was evident, but it didn’t stop him from supporting the Military Peace Establishment Act of 1802, which empowered him to build and educate army officers in the Republican mold through the establishment of a military academy. As Wood notes, this act “gave the president extraordinary powers over the new academy and the Corps of Engineers charged with its operation.”

“republicanizing” the Banks

Jeffersonian Republicans viewed Alexander Hamilton’s financial program as a vehicle for corruption, a tool of the speculator class that wielded financial power to exert influence. This was rich coming from Jefferson, whose own wealth was built on exploiting resources and enslaved labor.

The main battleground was the First Bank of the United States, which regulated state banks to prevent them from issuing more bank notes than their specie reserves could support—a measure designed to curb speculation and prevent economic collapse. However, Jefferson and his allies saw the Bank’s oversight as overreach.

As Wood explains, when the Bank was chartered in 1791, there were just four state banks. By 1800, there were twenty-eight, and that number swelled to eighty-seven by 1811 and 246 by 1816. This rapid expansion made central oversight increasingly difficult. Adding to the problem, many Americans—including Southern planters and Northern elites who lived off proprietary wealth—barely understood banking. The only real money was specie (gold and silver), but there was never enough to support the growing economy. As banks issued paper notes promising to redeem them for specie on demand, people became used to trading notes instead of redeeming them. This enabled banks to lend out far more than their reserves could actually cover.

When the Bank’s charter was approaching renewal, Treasury Secretary Albert Gallatin pushed for reauthorization. But Jefferson and the Republicans in Congress opposed it. By 1811, with the Bank’s charter set to expire (and Jefferson’s successor trying to keep the Jeffersonian tradition alive), it had little support left, even as the Treasury Department lobbied for its continued existence.

Ironically, dismantling the First Bank of the United States was a major win for state banks, which could now expand freely and issue notes without federal oversight. This liberalization of banking encouraged the commercialization of American society, particularly in rural areas where farmers and mechanics gained access to credit. But without a central regulatory structure, this freedom fostered irresponsible speculation and the boom-and-bust cycles that would plague the American economy.

Jefferson’s vision of democratization prioritized states’ rights over centralized authority. He once described Congress as a “foreign legislature” in terms of its influence over state commerce, going so far as to label it treasonous.

Most importantly, the bank wars wouldn’t end with Jefferson; they were just ramping up. We will track this development as we move into the presidency of James Madison and explore future reflections in the ensuing Oxford History of the United States volumes. But Jefferson’s shadow would linger over America for the rest of its history. A pattern of deregulating financial structures in the name of the “common man” had been established, even if that deregulation created a decentralized arena prone to cons, reckless speculation, and boom-bust cycles—leaving this same “common man” to bear the brunt of the consequences.

Final Note

Interestingly, Wood also notes that many Southern planters opposed the First Bank of the United States. However, he doesn’t fully address the structural reasons for this opposition: slaveholders desired a feudal-like society free from federal oversight, while still benefiting from global markets. This contradiction undercuts the idea that Jeffersonian Democrats (as some Federalist referred to them as) sought true democracy; their vision was one of control rather than inclusion.

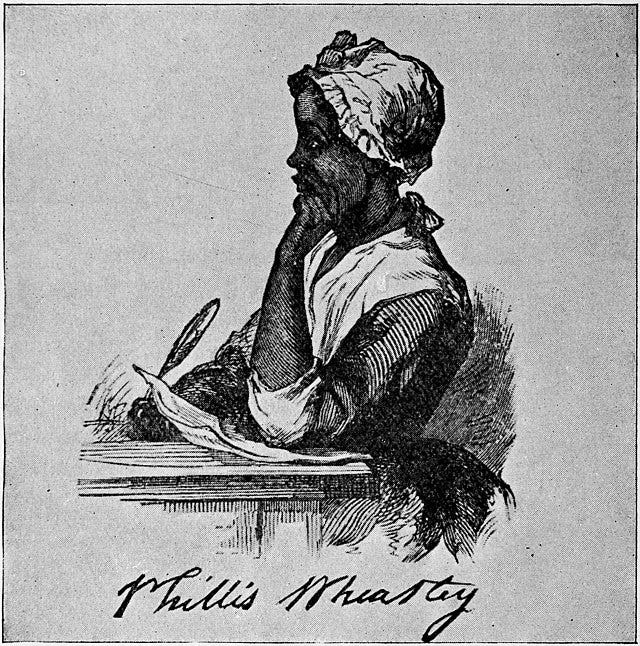

As we continue to explore this era, I will incorporate other perspectives—like those found in Phillis Wheatley and Imani Perry’s South to America—and examine another book, Sally Hemings, as part of this broader project.

Stay tuned.

You can find the South to America and Wheatley reflections here:

If you haven’t had a chance, check out my Monday post on the tragedies within the Black community caused by increasing classism, patchwork integration, and the destructive backlash masquerading as “principled conservatism.” This piece was difficult to write, but it’s necessary. Confronting our blind spots and reckoning with hard truths is essential today. For just five dollars a month, you can gain access to paid subscriber content that delves deeper into these complex topics:

Thank you for your continued support. Let’s keep moving forward.

This you have to read:

https://www.mind-war.com/p/orania-april-and-lessons-on-tyranny

Something for you . Live and learn

https://momentum.medium.com/why-white-people-dont-wash-their-chicken-a700f40d86ed