Phillis

On the Phillis in 1761, a young kidnapped African girl ended her journey to the British colonies on a continent referred to as the “New World.” The young lady had been sold from her home in Gambia or Senegal and traded to be a slave in budding colonies across the Atlantic Ocean.

But to where?

Would it be the commercial settlements in the South, Puritanical villages in the North, or a Catholic haven in Maryland?

As far as recorded history can tell, the Phillis sailed directly from Western Africa to Boston, Massachusetts. The eight-year-old girl survived a treacherous journey across the Atlantic but was seen as too feeble to work on plantations, so she stayed in Boston to serve domestically.

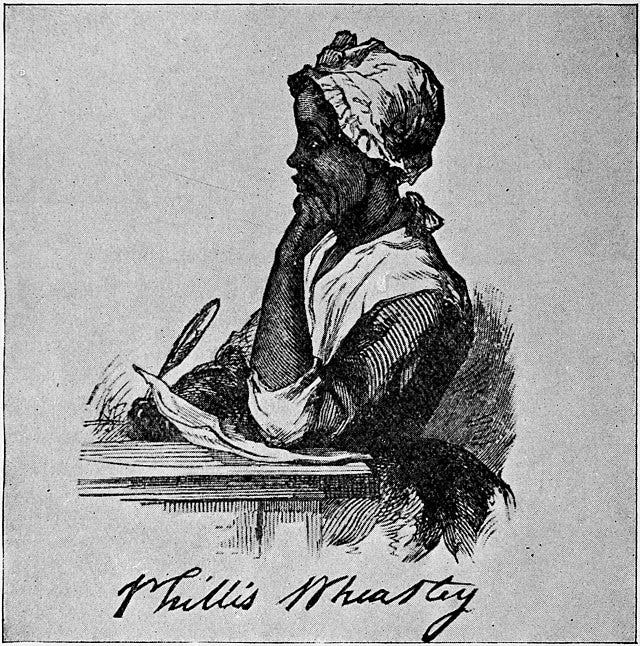

Thus, in this New England hotbed of religious and intellectual fervor, Susanna Wheatley, the wife of wealthy John Wheatley, bought a young slave girl. Though she was bought as property, the family tutored her after discovering her aptitude for letters. Eventually, the young slave developed a keen understanding of classical languages, such as Greek and Latin. The slave prodigy took the name of the ship she was brutally transported on, Phillis, and the surname of the family who bought her and provided her access to education, Wheatly. This name was destined to become the first African American poet.

Phillis’s first poem, On Messrs Hussey and Coffin, depicts her spiritual connection to nature and her working knowledge of Greek mythology. It was composed as she overheard the testimony of shipwrecked sailors eating dinner with the Wheatleys. Of course, she was in a role of servitude as she listened.

On Messrs Hussey and Coffin courtesy of the Phillis Wheatley Historical Society:

Did Fear and Danger so perplex your Mind,

As made you fearful of the Whistling Wind?

Was it not Boreas knit his angry Brow

Against you? or did Consideration bow?

To lend you Aid, did not his Winds combine?

To stop your passage with a churlish Line,

Did haughty Eolus with Contempt look down

With Aspect windy, and a study’d Frown?

Regard them not; — the Great Supreme, the Wise,

Intends for something hidden from our Eyes.

Suppose the groundless Gulph had snatch’d away

Hussey and Coffin to the raging Sea;

Where wou’d they go? where wou’d be their Abode?

With the supreme and independent God,

Or made their Beds down in the Shades below,

Where neither Pleasure nor Content can flow.

To Heaven their Souls with eager Raptures soar,

Enjoy the Bliss of him they wou’d adore.

Had the soft gliding Streams of Grace been near,

Some favourite Hope their fainting hearts to cheer,

Doubtless the Fear of Danger far had fled:

No more repeated Victory crown their Heads.Had I the Tongue of a Seraphim, how would I exalt thy Praise; thy Name as Incense to the Heavens should fly, and the Remembrance of thy Goodness to the shoreless Ocean of Beatitude! — Then should the Earth glow with seraphick Ardour.

Blest Soul, which sees the Day while Light doth shine,

To guide his Steps to trace the Mark divine.

Wheatley explores the theme of divine intervention in this work. She mentions Boreas, the Greek god of the northern winds, and Eolus, the Greek god of wind, as ways to personify nature and connect to her classical studies. She suggests the sailor’s survival is based on a more significant spiritual destiny. That sentiment is evident in the line, “Regard them not; - the Great Supreme, the Wise,/Intends for something hidden from our Eyes.” Here, Wheatley channels the idea of God’s divine plan, which we aren’t meant to imagine as mortals. The poet’s contemplation of heaven and hell is notable, as she concludes that faith in God dispels the fear of death. She writes, “Had the soft gliding Streams of Grace been near,/Some favourite Hope their fainting hearts to cheer,/Doubtless the Fear of Danger far had fled:/No more repeated Victory crown their Heads.”

This selection was sent to the printer at the Newport Mercury and printed on December 21, 1767. The editor’s note attached to the poem read:

“Please to insert the following Lines, composed by a Negro Girl (belonging to one Mr. Wheatley of Boston) on the following Occasion, viz. Messrs Hussey and Coffin, as undermentioned, belonging to Nantucket, being bound from thence to Boston, narrowly escaped being cast away on Cape-Cod, in one of the late Storms; upon their Arrival, being at Mr. Wheatley’s, and, while at Dinner, told of their narrow Escape, this Negro Girl at the same Time ‘tending Table, heard the Relation, from which she composed the following Verses.”

Notice the language of ownership and servitude when referring to Wheatley.

Celebrating America

Another Wheatley poem, "An Elegiac Poem on the Death of the Celebrated Divine George Whitefield," was published three years later and gained her widespread notoriety. In the poem, she celebrates George Whitefield, a quintessential figure of the first Great Awakening. Whitefield preached on spiritual equality, which included spreading the faith to enslaved Africans. This was novel, at the time, as Wheatly wrote in 1770:

Excerpt from Phillis Wheatley’s poem on the death of George Whitefield:

He offer'd THAT he did himself receive,

A greater gift not GOD himself can give:

He urg'd the need of HIM to every one;

It was no less than GOD's co-equal SON!

Take HIM ye wretched for your only good;

Take HIM ye starving souls to be your food.

Ye thirsty, come to this life giving stream:

Ye Preachers, take him for your joyful theme:

Take HIM, "my dear AMERICANS," he said,

Be your complaints in his kind bosom laid:

Take HIM ye Africans, he longs for you;

Impartial SAVIOUR, is his title due;

If you will chuse to walk in grace's road,

You shall be sons, and kings, and priests to GOD.

In 1773, Wheatley’s poetry was published overseas in a book titled Poems on Various Subjects, Religious and Moral, making her a trailblazer for African Americans. The book spurred Wheatley to travel to London, thanks to the funding of the English Countess of Huntingdon, Selina Hastings. It’s also important to note that the late Reverend George Whitefield was the Countess’s chaplain. While in England, she met with the Lord Mayor of London and visited the Tower of London. The book couldn’t be published in the colonies due to prejudice, but Archibald Bell, a London publisher, agreed to publish it as works dedicated to the Countess of Hereford. It's interesting how class works in both lands.

In a letter to Colonel David Worcester of New Haven, Connecticut, Wheatley describes her travels and her experience meeting abolitionists. Wheatley gained her freedom in 1773, as she writes:

“Since my return to America my Master, has at the desire of my friends in

England given me my freedom.”

Wheatley often celebrated influential contemporaries, including General George Washington. In late 1775, as the Revolution was brewing, she wrote To His Excellency General Washington, published in Pennsylvania Magazine. The work praised Washington for his leadership and is one of the earliest uses of “Columbia,” a deistic figure symbolizing American independence.

In her poem, Wheatley sees a spiritual mission undergirding the American Revolution. At the same time, numerous African Americans, enslaved and free, saw this moment as a period consumed by potentially limitless possibilities. The fervor of the revolutionary period spurred Black Americans to side with both the British and the Americans, hoping to gain freedom once the conflict ended.

Despite the British publishing her book and providing the means for her to attain freedom, Phillis Wheatley was pro-American. Jupiter Hammon, another early African American poet, wrote to Wheatley and urged her to focus more on spiritual matters. Hammon supported her work but differed from Wheatley in that he had been enslaved his entire life. Even though he had special privileges for a slave, being able to write and publish in New York, he remained an advocate against the institution of slavery. But he urged religious fortitude and patience for enslaved Americans rather than immediate action.

Hammon was much older than Wheatley and almost posed as a mentor-like figure. He was more reserved about the revolutionary attitudes taking over the American colonies and expressed loyalty to the family he served on Long Island. After Hammon's death, slavery would survive in New York for approximately two more decades.

Unfortunately, Wheatley hoped the energy of freedom would inspire the abolition of American slavery. However, America would not live up to its ideals then or in the future.

“One century scarce perform'd its destined round,

When Gallic powers Columbia's fury found;

And so may you, whoever dares disgrace

The land of freedom's heaven-defended race!

Fix'd are the eyes of nations on the scales,

For in their hopes Columbia's arm prevails.

Anon Britannia droops the pensive head,

While round increase the rising hills of dead.

Ah! Cruel blindness to Columbia's state!

Lament thy thirst of boundless power too late.

Proceed, great chief, with virtue on thy side,

Thy ev'ry action let the Goddess guide.

A crown, a mansion, and a throne that shine,

With gold unfading, WASHINGTON! Be thine.”

-Phillis Wheatley

Celebrating America When It Doesn’t Celebrate You In Return

Despite her belief in America, there is plenty to show that America did not believe in Phillis Wheatley.

After she attained initial notoriety, prominent white male leaders in Massachusetts couldn’t believe a Black woman could produce such masterful work. She was brought before 18 prominent Boston men, including John Hancock, to scrutinize her intellectual abilities patronizingly. After proven, the men signed an affidavit stating: “We whose names are under-written, do assure the world that these poems ... were written by Phillis, a Negro girl, who was but a few years since, brought an uncultivated Barbarian from Africa…”. This signed statement became the forward for her poetry book to be published in London.

Thomas Jefferson saw Black women as fit to procreate with but not fit to be writers. In his Notes on the State of Virginia (1785), he stated that her work was “below the dignity of criticism.” The pattern is apparent in Jefferson as he argued that the intellectual inferiority of Africans justified the system of chattel slavery. White historians of the 19th century would notoriously downplay or ignore Wheatley’s contributions.

Sadly, Wheatley failed to publish a second poetry book as publishers grew weary of supporting an African American woman. To make matters worse, her husband, John Peters, another free African American and grocer, was imprisoned for debt, which made matters even dire. The structural prejudice and the circumstances of her personal life drove Wheatley to become a scullery maid to support her family. She died of illness in 1784. Her infant died soon after. They were buried in an unmarked grave.

Constant Renewal

A nation that relentlessly wishes to remake itself and stay youthful also forgets its history and acts irreverently toward it. Phillis Wheatley believed in a country that didn’t believe in her. She is a giant whose shoulders many of us African Americans stand on. But her story also reveals a dark pattern of Black Americans believing in progress and being met with volatile and demeaning resistance. America’s national pastime of renewing itself in a way that railroads the contributions and stories of marginalized groups has weakened our nation’s ability to learn and evolve. Unfortunately, the urge to dismiss the history, experiences, events, and memories of Americans of color is perpetuated into the present as democracy is challenged through the language of racial hatred. The degradation is aided by mainstreamed (predominately white) storytellers’ overt and subconscious failure to make these logical connections when wondering how a mighty, superficially democratic superpower has fallen from grace.