Mr. Jefferson’s Family Gathering

Imani Perry tells a haunting story in South to America that lingers in the mind like an unquiet ghost. In 1812, in the Kentucky mountains, a fifteen-year-old enslaved boy named George dropped a water pitcher. His owner, Lilburn Lewis, the nephew of Thomas Jefferson, responded with unimaginable cruelty. Perry writes:

“There’s a historical event that haunts and shames the region. And shows the machine of power. The story is about a boy named George. George was owned by Lilburn Lewis, the nephew of Thomas Jefferson, in the Kentucky mountains. In 1812, a cherished water pitcher slipped from the fifteen-year-old George’s hands, and it shattered. In a drunken rage, Lilburn and his brother tied George to the floor of the kitchen and told other slaves to build a fire. They did and cowered. The master struck George across the neck with an ax, then commanded one of his fellow slaves to cut him up dead. Bit by bit, George’s body was burned in the fireplace. As his body burned and blackened, an earthquake hit in the middle of the night. The chimney collapsed, snuffing the fire.”

-Imani Perry, South to America

Natural forces undermined an attempt to bury this brutal murder as aftershocks unearthed the boy’s body, culminating with a dog carrying George’s skull into the United States’s fabled main street. Perry’s account of George’s fate exposes the brutal underbelly of the planter class and challenges the enduring myth of Southern gentility.

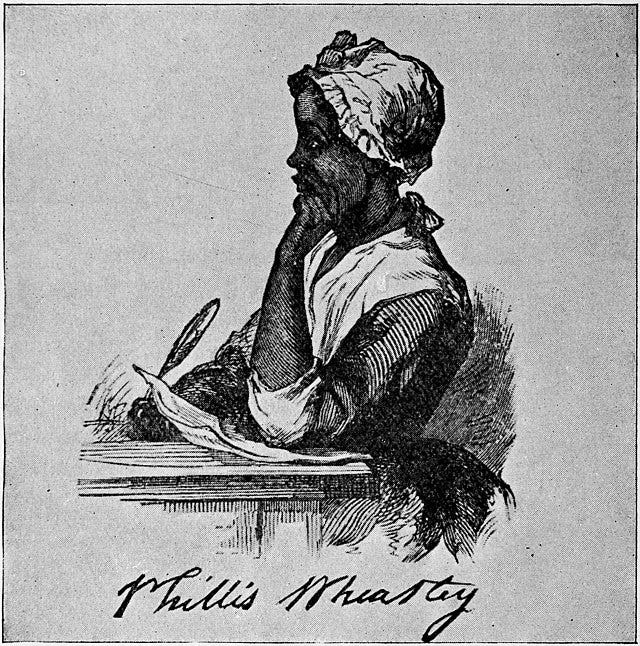

Last week, this blog unpacked the life of Phillis Wheatley and referenced Thomas Jefferson’s demeaning view of her artistic prowess. You can read the post here:

Before that, I reflected on Gordon S. Wood’s Empire of Liberty and the rise of the Jeffersonian Republicans as a force demanding limited government. At the same time, the Federalists worked to refine their belief in a strong national government. The anti-federalist forces saw their poster child in Thomas Jefferson who preached individual liberty. Ultimately, the Federalists lost power, and America experienced a peaceful transfer of power:

The Peaceful Transfer

Consequently, the Jeffersonian “Revolution of 1800” has blended nearly imperceptibly into the main democratic currents of American h…

Today, I reflect on Empire of Liberty and South to America. Gordon S. Wood’s theme of gentlemanly leadership as a driver of late 18th-century and early 19th-century political norms can be foiled by the way Imani Perry exposes the fiction of genteel leadership.

Wood writes about the idealism of the founding generation, which manifested in beliefs that disinterested gentlemen should run the government with no business ties and enough leisure time to make unbiased, nonprovincial decisions about a national force. The historian explains how this belief slowly unravels as political life becomes more accessible. The relative proliferation of media and rising partisanship chip away at the honor of gentlemen leaders, who increasingly disagree in the public eye and not exclusively in the presence of distinguished company. However, Perry offers a different perspective. One that is centered on the experiences of enslaved African Americans.

Jefferson wrote of liberty and individual rights and inherited his wealth and power from an enslaved underclass. He is also the uncle of the Lewis brothers, who were ruling class members but relied on violence to maintain their position, even as it cloaked itself in the rhetoric of virtue. The story of George lays bare a truth that America has long struggled to acknowledge: the supposed refinement of its early leaders was built upon brutality. The myth of the gentleman, like so many myths of American exceptionalism, serves to obscure the raw, ugly reality of power. The “founding fathers” were not just architects of democracy; many were also architects of a carefully crafted illusion—one that allowed them to justify their own moral contradictions.

That illusion still shapes our historical memory today.

Shame

One of the most chilling aspects of Perry’s story is that the Lewis brothers did not collapse under the weight of guilt. They collapsed under the weight of exposure. Their crime was only intolerable once it became known. This distinction is crucial—not only for understanding the past but for recognizing how power operates today.

In my recent Monday Thought post, I discussed the limited imagination in political discourse—how power structures shape what is considered morally unthinkable rather than simply embarrassing.

Monday Thought: The Limits of Imagination

"Never be limited by other people’s limited imaginations." — Mae Jemison

The Lewis brothers’ fate is a historical example of this dynamic. The act of slicing a slave boy’s neck open with an axe wasn’t what caused the Lilburn brothers to unravel; it was the revelation to the public.

How often do we see this same dynamic today? Scandals rarely hinge on whether something is wrong but on whether it can be hidden. The outrage is not over injustice but the breach of decorum that reveals it. This is why history remains so contested. America does not mind its injustices nearly as much as it minds being forced to acknowledge them. The same impulse that drove the Lewis brothers to burn George’s body is the impulse that fuels modern historical revisionism—removing uncomfortable truths from textbooks, sanitizing national myths, and reframing systemic oppression as unfortunate but necessary. But just as George’s skull kept resurfacing, so too does the past, no matter how often it is buried.

The Past Has Not Passed

Oh, nothing, just my favorite Disney film and its deep connection with my respect for the truth of the past and how it haunts and informs us. I’m not embarrassed to admit this scene brings me tears:

Perry’s excerpt is a metaphor for the nation’s long struggle with historical memory.

“This drew the attention of townspeople, who soon found out what happened. Disgrace fell on the family. The Lewis brothers, who were supposed to be gentlemen, were revealed to be excessively violent. One died by suicide; the other disappeared. The horror of killing is something the Lewis brothers could live with; the shame of that skull coming back up and up, they could not. They were of the planter class, not commoners. Shame was not supposed to be theirs.

The trill of history: On the surface, Lewises were genteel and grace-filled figures, maybe flowed but noble. Underneath them, the ones who labored were uncouth, rough, maybe only part human or maybe horrifically debased. The myth of surface gentlemanliness was a sly fiction then; it is certainly understood as a loud fiction now. But still, we don’t hold it up to the light nearly enough. Gentlemen were not gentlemen at all.”

-Imani Perry, South to America

Perhaps the most haunting part of this story is not just the horror of George’s death, but the realization that history itself is alive. It does not rest in archives or textbooks. It lingers in landscapes, in institutions, in cultural memory. It rises, again and again, demanding to be seen.

Widening our gaze to understand our society for its greatness and tragedy makes the present moment less shocking. It equips us in a way where we can join the rest of the world in an imperfect manner and not lord over it with a false sense of exceptionalism. America must outgrow its denial of the universal forces of history.

Thank you for detailing the horrors, while some work hard to hide them.