Consequently, the Jeffersonian “Revolution of 1800” has blended nearly imperceptibly into the main democratic currents of American history. Jefferson himself was sensible of his inability to accomplish “all the reformation which reason would suggest and experience approve.” He was not free to do whatever he thought best, he said; he realized how difficult it was “to advance the notions of a whole people suddenly to ideal right,” and he concluded “that no more good must be attempted than the people will bear.” Still, when compared to the consolidated heroic European-like state that the Federalists tried to build in the 1790s, what Jefferson and the Republicans did after 1800 proved that a real revolution—as real as Jefferson said it was—had taken place."

— Gordon S. Wood, Empire of Liberty

Jefferson in the Opposition

Thomas Jefferson was a man who could afford lofty ideals detached from present reality. He inherited his father's slave labor and thrived on the wealth he exploited by owning other human beings. He was not as involved in the on-the-ground traumas of the American Revolution, for he was not in military service during the war. And as the Articles of Confederation collapsed, he had high-intellectual conversations with other Enlightenment thinkers a continent away. Jefferson’s experience differs from that of Alexander Hamilton, who was George Washington’s aide-de-camp during the war years and was on the frontlines of financial debates as the first attempt at governing crumbled for the founding generation. Still, Thomas Jefferson was a cunning idealist who practiced cunning pragmatism when no one was looking. The diverging perspectives informed the differing views of America’s future within the larger public domain.

As secretary of state during President Washington’s first term, Jefferson was at odds with the official position regarding neutrality in the U.K.’s and Revolutionary France’s post-beheading war. Jefferson initially supported neutrality but had more sympathy towards France, where his ideas of popular government were more aligned. The ensuing fallout occurred when the future president cultivated a diplomatic relationship with Edmond-Charles Genêt, the French ambassador to these United States, who attempted to bring the U.S. into the war effort on the side of France. Washington and Hamilton viewed this as a misstep, with Washington declaring a Proclamation of Neutrality and calling on France to recall their ambassador.

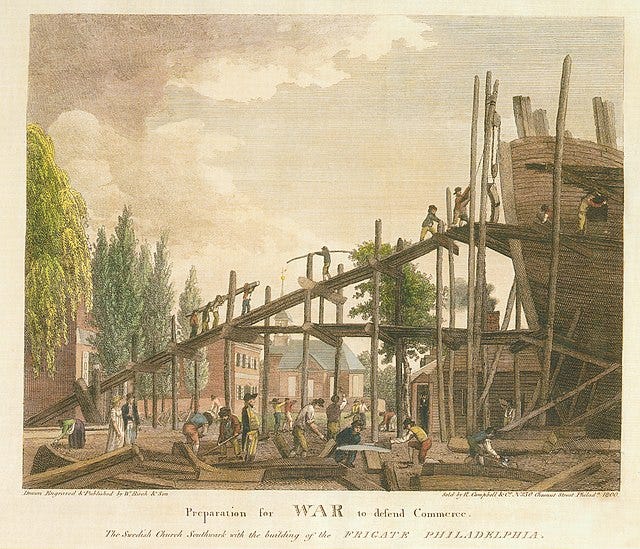

Even the administration’s domestic policies were causing Jefferson to face internal conflict with the president’s consensus as his lofty idea of American society evolving into a land of subsistence farmers became threatened. I know. The fact that a person who owned other farm labor as property was spreading utopian ideas about independent, self-sufficient farmers is something to behold. However, it makes sense when considering Jefferson’s luxurious detachment as a factor of his idealistic worldview, especially when compared to Hamilton’s experiences of rising through the ranks from humble beginnings in the exploitative commercial landscape of the Caribbean and how that factored in the first treasury secretary’s intense pragmatism and predilection for commerce. In the beginning, Hamilton’s worldview was prioritized.

I reflected on the Federalist Program and its push for central banking and manufacturing tariffs.

Reflections on The Federalist Program

I photographed the Inner Harbor as the sun lowered into the distant horizon. Standing before the Maryland Science Center, I thought about times I would visit the building as a child and adult. It has been a staple of my life, but that can’t be said for every generation. The Maryland Science Center began a…

Jefferson viewed rising financial institutions like the First Bank of the United States as a way for financial speculators to seize state power through patronage. The keen philosopher was not wrong. With his populism, despite his hypocritical lifestyle, the well-red third president became the poster boy of democratic promise, which would transcend his imperfect being. Jefferson did not want to recreate the commercialized society of Great Britain. He was frustrated that Hamilton’s plan for federal assumption of state debts only favored financial grifters who made bad bets and could rely on a connected government run by the wealthy to pay them back. After all, Jefferson was governor of Virginia, a state that eventually paid its Revolutionary War-era debts. Even though, in his personal life, Jefferson struggled.

Jefferson’s ideological distance from the Washington administration and public persona made him the ideal figurehead for the emerging Jeffersonian Republican party (as they were referred to at the time) or the Democratic-Republican party (more commonly used today). His stance against the Federalist policies intersects with the rise of America’s “middling” group of laborers (as Wood puts it), who were not of aristocratic birth but financially successful and usually were artisans, merchants, and/or prosperous farmers in the North. These middling groups resembled the modern middle class and symbolically became the foot soldiers for popular democracy. The Jeffersonian appeal in the South was traditionally concentrated in the slave lords who spoke for their populations with a broad brush and feared federal intervention regarding their slave-based wealth. Some things seem never to change.

A Peaceful Precedent

By 1800, Jefferson was to be president after years of loudly voicing his opposition to Federalist policies. For example, his stance on the Alien and Sedition Acts manifested in his Kentucky Resolution, which argued that states could ignore unconstitutional federal laws. The logic was that the state governments were in a pact agreement with the national government and could nullify their side of the bargain when that pact wasn’t honored on the federal side. James Madison offered a more measured resolution that lacked Jefferson’s righteous thunder.

Also, note how Jefferson was Adams’s vice president at the time!

Alienation: The Rise of the Vice Presidential Curse

Growing up, I attended the same elementary/middle school as my older sister. It was a Catholic school that was highly family-oriented. I ha…

For Jefferson to assume the presidency meant ideological resistance to the Federalists was now enshrined in power. Jeffersonian Republicans were elected to the House of Representatives, state legislatures elected them to the Senate, and the Electoral College handed the reins over to TJ. Clubs supporting the Democratic-Republicans had sprung up nationwide and promoted Jeffersonian politics. Similar to how Masonic lodges supported Federalists but not in a way that engaged in retail politics (as the Jeffersonian Republicans had begun doing).

The democratic tide of the late 18th century strengthened Jefferson’s resistance to centralized government and solidified the Democratic-Republican Party as the primary opposition to Federalist rule. This rising coalition took control of the government from John Adams and the Federalists without an organized effort to retain power through violence or disunion—a remarkable event in an era when political transitions were rarely peaceful. In the autocratic world of 1800, this was a miracle. Across the Atlantic, the French Revolution had devolved into bloodshed, executions, and military dictatorship, reinforcing the unique nature of America’s peaceful transfer of power.

The late 1790s in America were mired by partisan upheaval. Writers were jailed, and the possibility of revolt profoundly resonated in the imaginations of a rebel generation.

A smooth landing was not guaranteed.

Reader Question

Is America still capable of such a peaceful transfer of power in the face of deep political divisions?

Is America still capable of a peaceful transfer of power? That question was answered on Jan 6, 2021

Trump did not attend the swearing in and only reluctantly left the White House after taking everything but the desk with him.

The only way Trump will leave this time is feet first on a gurney, and JD Vance will step up.

Another great piece Steward. I look forward to more.

A tidbit about Jefferson, he really did sour on democracy. He traveled to Pittsylvania County, VA and sat in on a business meeting in a Baptist church to get some experience as to how the"middlings" did it. By the way I found that term interesting, there was no such thing as a middle class, there were merchants, labors, free men, servants, and nobility or quasi nobility. When Marx wrote his tiresome screeds, there was no such thing as a middle class, so he used the word bourgeoisie for that purpose.

Back to Pittsylvania Co,. He watched the meeting devolve into shouting, arguments and near into fisticuffs and walked away disabused of democracy for the "middlings".

Democracy was fine for the cultured, property owning elite, and thus his Democratic Republican Party, was, as was the Constitution, written for propertied men, color not mentioned. In fact free black men did vote in the first two elections And it wasn't until 1807 that New Jersey passed a law that only white men could vote.