Alienation: The Rise of the Vice Presidential Curse (Empire of Liberty #2)

Eventually the only alien was John Adams.

Growing up, I attended the same elementary/middle school as my older sister. It was a Catholic school that was highly family-oriented. I had friends who also had older siblings in my sister’s grade. We all had counterparts in different grades that allowed our teachers to associate patterns. It was mostly a pleasant environment. However, I was always known as my sister’s younger brother! Trust me, I am proud of that fact. However, this experience helped me as I analyzed the presidency of John Adams and the fallout of the Alien and Sedition Acts. Vice presidents who become president due to the tremendous impact of their predecessors often have a legacy to uphold.

Vice presidents who ascend to the presidency often find themselves struggling to define themselves as the shadow of their titanic predecessors looms large. John Adams’s presidency is a prime example of this phenomenon, as his tenure was characterized by partisanship, his philosophy of gentlemanly leadership, and the pressures of navigating Federalist overreach. Following the towering legacy of George Washington, Adams inherited a nation beset by internal divisions and external crises. Ironically, many of these challenges stemmed from the underbelly of policies championed by the previous administration. In time, Washington’s enduring glow would obscure the more contentious aspects of his presidency.

Let’s take a step back for a moment. George Washington’s presidency established the template for the executive branch, with his stature lending the office a near-monarchical aura. As Gordon S. Wood notes in Empire of Liberty (2009), many Federalist elites viewed Washington as a figure of majesty, a stabilizing force who commanded universal reverence. Yet even Washington faced challenges, including the 1794 Whiskey Rebellion, when western farmers revolted against Federalist excise taxes. A national militia put down the rebellion, but resulted in heightened Federalist paranoia about democratic rhetoric and influences challenging established hierarchies. For Jefferson and Madison, the way the uprising was handled symbolized another step towards a centralized government threatening the liberties of individuals and states. Thus, by the end of his presidency, Washington was disillusioned and exhausted, warning against political factions in his Farewell Address. Despite these misgivings, Washington’s leadership style created an expectation of executive strength that Adams struggled to fulfill.

Adams’s rise to the presidency coincided with the waning days of the French Revolution. Federalists, led by Alexander Hamilton, sought closer ties with Britain to sustain the financial system they had built. In contrast, Democratic-Republicans, led by Thomas Jefferson and James Madison, championed France’s revolutionary ideals as they aligned with their more populist vision of governance. Adams’s philosophy made him a disinterested gentleman who aimed to rise above partisan squabbles. Educated as a gentleman and deeply committed to the ideals of balance and reason, Adams believed the executive branch should act as a stabilizing force, unyielding to the passions of the public or the machinations of party politics. This view, however, often left him isolated and out of step with the realities of the emerging two-party system.

Nowhere was the tension between Adams’s philosophy and Federalist pressures more visible than with the Alien and Sedition Acts of 1798. Comprising four laws—the Alien Enemies Act, the Alien Friends Act, the Naturalization Act, and the Sedition Act—this legislation was driven by Federalist fears of French influence and growing domestic unrest. The Alien Enemies Act allowed the detention of male citizens of enemy nations during wartime, while the Alien Friends Act empowered the president to deport non-citizens deemed dangerous. The Naturalization Act raised the residency requirement for citizenship, curbing immigrant political participation, and the Sedition Act targeted publications critical of the government. Federalists framed these measures as necessary for national security but also aimed to weaken Democratic-Republican opposition. The partisan political gamesmanship, once viewed as anathema to the founding generation, became an American mainstay.

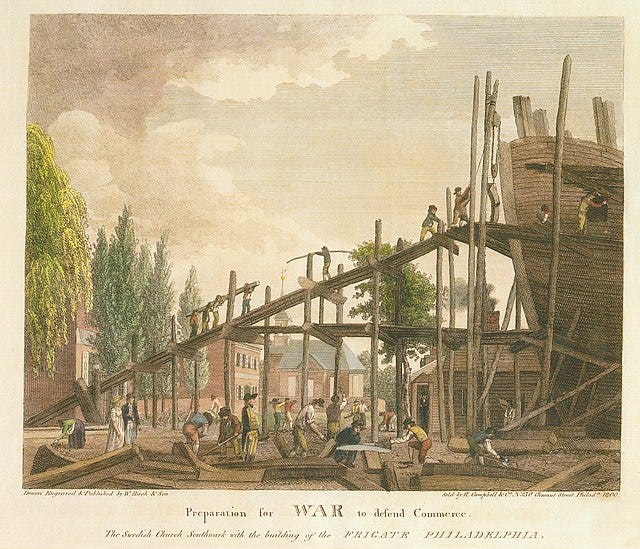

Adams’s role in the Alien and Sedition Acts highlights his complex position within the Federalist establishment. While he signed the acts into law, he added a sunset clause to the Alien Friends Act, allowing it to expire in 1800. Adams saw enforcement as part of maintaining stability, but he resisted the more extreme Federalist demands, such as Alexander Hamilton’s push for a standing army and aggressive actions against France. The proposal led to the appointment of George Washington as Lieutenant General of the so-called “'New Army.” Still, the force was never organized, and the mismanagement of the effort only deepened Washington’s disillusionment. This episode underscored the growing divide between Adams and the more radical Federalists, highlighting his reluctance to embrace their expansive vision of executive power.

Ultimately, Adams’s measured approach alienated his party and opponents, leaving him politically isolated. The second president’s maverick nature was evident in Adams’s decision to pursue peace with France, ending the Quasi-War. Despite hawkish calls for military escalation by the Federalists, Adams dispatched diplomats to negotiate with France, defusing tensions and avoiding a potentially disastrous conflict.

Wood writes about Hamilton’s appeals to delay the envoy:

“In October 1799 Hamillton, whose own highstrung temperament was being stretched to the breaking point, made a last-ditch effort to delay the mission by arrogantly lecturing the president on European politics and the liklihood of Britain’s restoring the Bourbons to the French throne. ‘Never in my life,’ Adams recalled, ‘did I hear a man talk more like a fool.’ (Of course, in 1814-1815 Britain and its allies actually did restore the Bourbon king Louis XVIII to the French throne.) Finally, by early November 1799, Adams was able to get his envoys off to Paris.”

Though wise in hindsight, this decision further divided the Federalists, as many saw it as a betrayal of their interests. For Adams, it was a gentlemanly stand, consistent with his belief in the executive’s role as a neutral arbiter.

Adams’s experience set a precedent for vice presidents who ascend to the presidency. Unlike Washington, who commanded near-universal respect, Adams lacked the popular appeal and bipartisan goodwill to unite the nation. His intellectual rigor and commitment to principle often came across as aloofness, making him ill-equipped to manage the growing partisanship of the era. Moreover, as the first vice president to succeed a universally revered leader, Adams bore the weight of expectations while contending with the fallout from policies he had not entirely shaped. This dynamic of inheriting both the mantle and the challenges of a predecessor has remained a recurring theme in American history, from Martin Van Buren’s struggles after Andrew Jackson to Lyndon B. Johnson’s fraught tenure following John F. Kennedy.

The second president’s tenure reflects enduring tensions in American governance: the balance between security and liberty, the difficulty of leadership in a divided nation, and the limits of personal philosophy in the face of stiff political realities. His story is a reminder that the presidency is a position of immense power and a crucible for the individual who holds it. Caught between Federalist pressures, his own ideals, and the demands of the moment, Adams emerges as a tragic figure whose legacy was only fully appreciated long after his time in office.

excellent Steward, well written, thank you and I have learned a lot. This is a keeper. I have a much better picture of John Adams now.