Baked Into the Pie (Empire of Liberty #10)

What Gordon Wood’s Early Republic Reveals About Our Present Crisis

You may begin to notice a shift in how these pieces are structured. The main body, the historical grounding, and the context, will remain free for all subscribers. I believe in open access to deep thinking, and I want these explorations to reach anyone who finds value in them.

But as I move toward the closing reflections, where the past breathes into the present, and I begin to ask harder, more personal questions, that space will now live behind the paywall.

This is not to gatekeep insight, but to sustain the kind of writing that takes time, energy, and a clear-eyed sense of purpose. If you’ve found something in these pages that stays with you, I hope you’ll consider supporting the work.

Because the final stretch, the stretch into meaning, is where the risk lives. And it’s where I want to grow.

Jeffersonian America

Jeffersonian America was rife with competition, commercial appetites, class resentment, and violence. The democratic ethos associated with Jefferson, often tapped in an idealized register, was not shared by all. But the words—democracy, rights, liberty—meant something, especially to people who had just fought a war over autonomy. The convergence of political resentment against a Federalist elite and the expansionist hunger to settle lands already occupied by Indigenous peoples created a volatile mix, one that echoes in the glorification of crassness we still see in America today.

Gordon S. Wood traces these developments in his sweeping examination of the early American republic and its Jeffersonian transformation.

Last time, the newsletter explored Jeffersonian America’s growing pretension for commerce, and the other side of that coin: greed.

Check it out and other Empire of Liberty reflections:

The Inland Fracture of the Federalists

Charles William Janson, an English immigrant to the U.S., eventually returned to England after a string of land speculation and business failures. Bitter, he insulted American society as ignorant and crude, where the uneducated believed themselves equal to the educated.1 In that insult lay the energy many Federalists were channeling as Jefferson’s presidency progressed. Concentrated increasingly in the Northeast, Federalists viewed the rest of the country as savage, selfish, unkempt, and dangerously egalitarian.

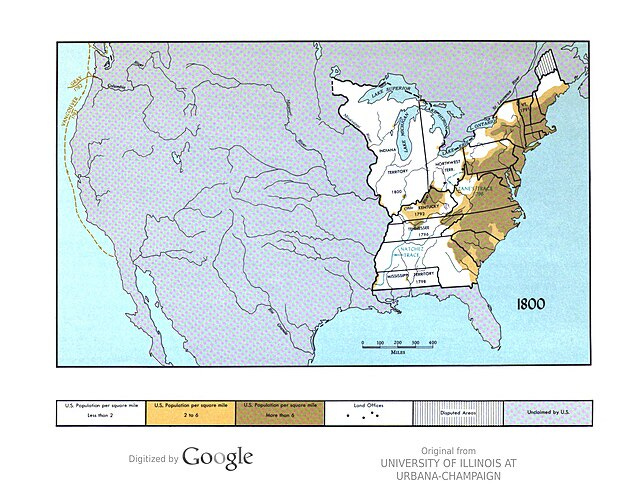

Though a strong Jeffersonian Republican (or Democratic-Republican) presence existed in the North, especially in inland and western regions, Federalist influence in those areas was fading quickly by the first decade of the 19th century.

Yet one notable Federalist, William Cooper of Otsego County, New York, managed to establish himself inland. He founded the town of Cooperstown, now known for the Baseball Hall of Fame, in hopes of becoming a gentleman in the old European sense: a landowning patriarch. But that vision was no longer aligned with the American way.

Soon after its founding, Cooperstown was plagued by lawsuits, bankruptcies, vandalism, arson, and violence. The town’s disdain for aristocratic pretense culminated in Cooper himself being publicly caned in the street in 1807.2 His children were ravaged by illness, greed, alcoholism, and recklessness. Only one, James, who later became a novelist (one of whose literary works is depicted by the artist above), survived with any legacy. Even then, the family lost its wealth, and Cooperstown was bought by what Wood calls “a new breed of upstart”: William Holt Averall, the son of a shoemaker and a hard-nosed capitalist who rejected any investment in gentility.3

Violence, too, became political. Proto-parties (not yet formalized) regularly saw opponents physically beaten, sometimes fatally. The cane and the pistol, not just the pamphlet, were often the tools of ideological conflict.4

In that chaos, the Federalist worldview—that some were born to govern and others to be governed—was breaking down. Amid the fever of change, elites began to sell the idea of democracy, even if they had no intention of living by it.

You can read more about that here:

Southern Culture and Savage Irony

Violence was no stranger to the South either, but there it became more than common—it became defining. The emerging Southern honor culture was mirrored in bloodsport: dueling, gambling, cockfighting, and reckless moneymaking. Southern elites sneered at these pursuits even as they partook in them.

Andrew Jackson, the son of Scots-Irish immigrants from Northern Ireland, personified this violent honor culture. Jackson was known for his love of racing and cockfighting, and for killing a man over a horse race wager. That same man would become one of America’s most consequential presidents.

Wood shows how New England Federalists metaphorically and geographically looked down on Southern Whites, describing them as barely better than their "savage neighbors"5—a reference to Indigenous Americans.

Violence in the Southern backcountry was often grotesque. Gouging out eyes and biting off noses were not uncommon. These brutal customs, as Wood and others argue, were inherited from the Celtic borderlands of the British Isles. As he writes:

“Indeed historians have persuasively argued that most of the characteristics of the Southern ‘rednecks’—including their indolence, the making of ‘moonshine,’ fiddling and banjo-playing, chewing tobacco, hunting, and hog-raising—can be tracked back to their Celtic ancestors. This is especially true, they say, of the hot-headedness and propensity to personal violence of backcountry Southern ‘crackers,’ with someone like Andrew Jackson being a prime representative.”6

To foreign observers, Americans pushing westward and down the Ohio River weren’t spreading civilization—they were regressing into savagery.7

And this doesn’t even account for the day-to-day brutality experienced by enslaved African Americans. That cruelty was not incidental; it was structural, and it was foundational.

You can read more about that here:

The Hypocrisy of Republicanism

“With the disappearance of indentured servitude, black slavery became more conspicuous and more peculiar than it had been in the past, and hired white servants resisted any identification with black slaves.”

As hierarchies unraveled, so too did the carefully maintained illusions of racial order. In one telling anecdote, a foreign visitor mistook a White woman for a servant. She insisted she was merely “help,” noting, “I am no sarvant; none but negers are sarvants.”

White domestic laborers demanded to be seated at the table with their “bosses”—a word increasingly adopted from Dutch usage. They claimed such proximity was not only natural but righteous in a free country. This growing refusal to be deferential contributed to a market society in the North, where masters and journeymen began to regard each other as employers and employees. The rise of impersonal cash wages signaled the rise of wage labor and added energy to the Northern Jeffersonian Republican base.8

As Wood notes, Thomas Jefferson, enslaver and President, believed the Republic belonged to people who lived by manual labor, not by their wits. That’s a rich irony, given the source of Jefferson’s own wealth. But more cynically, Jefferson knew how to politicize that belief, because that sentiment animated the voters in his Northern strongholds.

Federalists, who saw themselves as a kind of American aristocracy, viewed this labor populism as a threat to their vision of order and refinement.9

The deeper hypocrisy came from the so-called Southern cavaliers, who cast themselves as working men while living in luxury—men who, in the words of contemporary critics, had only been taught to “dress, to drink, to smoke, to swear, to game” and indulge in “the very rational, elegant and humane pleasures of the turf and cock-pit.” These critiques came from lawyers in Virginia aiming to wrest control of county courts from the planter class.10

Thus, the mythology of the working-class hero was born—often more fantasy than fact, but politically potent all the same.

The next section shifts from history into reflection, connecting the fractures of Jeffersonian America to the disillusionment of our present moment. It’s where the threads come together, where the echoes get louder, and where the questions get harder.

If you’ve made it this far and want to keep exploring how the past haunts the present, I hope you’ll consider becoming a paid subscriber. That support unlocks the full piece and helps sustain work that doesn’t just analyze history, but wrestles with what it all means.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Nothing New Under the Sun to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.