A twisted, inverted fairy tale took home Best Picture at this year’s Academy Awards, and that’s precisely what Anora delivers. Directed, written, and edited by Sean Baker, the film is a raw and haunting exploration of power, wealth, and exploitation—one that will be discussed for years to come. At the heart of it is a stunning performance by Mikey Madison as Anora, or Ani, a dancer at a Brooklyn gentlemen’s club. Fluent in Russian, she’s assigned by the club’s manager to entertain a group of Russian guests, leading her straight into the orbit of Vanya (Mark Eydelshteyn), the reckless, spoiled son of a Russian oligarch.

Vanya is supposed to be studying in America, but instead, he’s indulging in a consequence-free playground of wealth, partying with the abandon of someone who has never had to face the real world. Ani, ever shrewd, seizes the opportunity to milk him for as much cash as possible—until she starts to believe there may be something more between them. At the peak of his debauched, drug-fueled escapade, Vanya marries her.

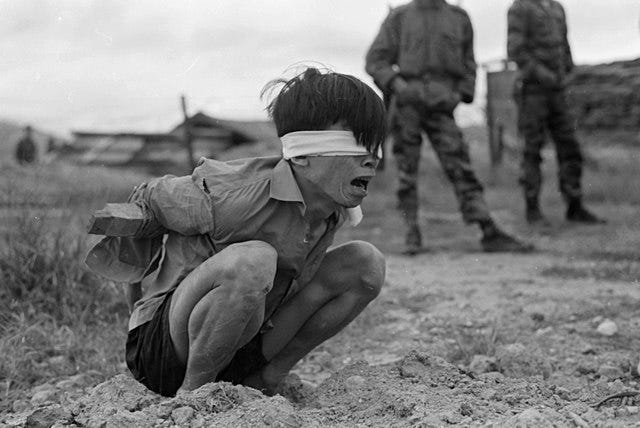

Blinded by the allure of wealth and a way out of her current life, Ani convinces herself that her days of dancing and grinding on predatory men might soon be replaced with high society and luxury. But reality comes crashing in. When Vanya’s godfather, acting on behalf of his powerful parents, learns of the impulsive marriage, he and his henchmen storm the father’s mansion to force a divorce. Vanya, true to form, abandons Ani without a second thought, leaving her to be manhandled and humiliated by his family’s enforcers.

Eventually, Vanya is found back at the same club, entertained by Ani’s rival, as if nothing had happened. By then, Ani has realized it was all an illusion. I wished she had managed to secure enough money to build a better future rather than waiting for Vanya’s call, but emotional whiplash kept her tethered to the fantasy. The divorce is finalized in a devastating scene where, for perhaps the first time in the film, Vanya is fully sober—both literally and figuratively. When Ani pleads for him to tell his parents he loves her, he coldly asks if she was ever really that naive. One of the henchmen, almost as an act of pity, returns Ani’s expensive diamond ring. What follows is the film’s most brutal moment: she has sex with him in the car, in front of her childhood home, before being dropped off, where she finally breaks down in tears.

This moment encapsulates the grim cycle Ani is trapped in—a world that values her only for sexual entertainment, a value she has been conditioned to internalize. By the end, she is left emotionally scarred, used, and discarded, yet still reaching for scraps of validation in the only way the world has taught her to seek it.

One of the film’s greatest strengths is how it humanizes sex workers without romanticizing their struggles. Ani is a survivor, navigating a brutal reality where the rich can dispose of people at a moment’s notice—whether it’s hotel workers evicting guests to make room for someone wealthier or sex workers being used in dehumanizing ways for a price.

Anora is haunting, unflinching, and unforgettable. I highly recommend it.

Be sure to check out my previous Friday posts:

The Franchising Machine 2013

Riddick (2013) is a typical early 2010s blockbuster, one that was clearly made before the reckoning of the Me Too movement. The film’s only prominent female character is hyper-sexualized and exists primarily through the lens of Riddick’s affection, rather than having an authentic narrative of her own. This was the first thi…

I Watched 12 Years A Slave for the First Time

Greetings! This blog will have new posts twice a week on Thursdays and Fridays. Posts will be between 5 p.m. and 6 p.m. on Thursdays and between 7 a.m. and 8 a.m. on Fridays. One post will revolve around a book I am currently reading. The other post will revolve around a film that I have watched. Tomorrow, I will share my observations on Alexander Hamil…