The Call of the Oscar

Oscar season is upon us, and we can tell because of the buzz surrounding Emilia Perez (2024). Frenchman Jacques Audiard directs this Spanish-language French crime musical and has been nominated for Best Director by the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences. The film has racked up 13 Oscar nominations, one less than the record of 14 set by All About Eve (1950), Titanic (1997), and La La Land (2016). However, over the last few weeks, unscathed bigotry and insensitivity have mired the film's Oscar-bait public relations tour.

The film's premise is that a former cartel boss transitions from a man to a woman to begin a new life away from the darkness his work entails. This alienates the boss from his family but is rationalized as a form of protection. Simultaneously, bodies of missing Mexicans begin to be dug up from the ground, which spurs the former cartel head to start a foundation that seeks to connect loved ones to the recently unburied.

A star-studded cast, including Zoe Saldaña, Selena Gomez, Karla Sofía Gascón, Adriana Paz, Édgar Ramírez, and Mark Ivanir, contribute to the film’s overall glow.

Style

First, Emilia Perez is stylistically gorgeous. The colors are vibrant, especially when scenes smoothly transition into a musical moment. The production value of this film is also top-notch, which is to be expected. The mise en scène depicts mansions, surgical offices, and relief centers in a fast-moving and fluid manner, allowing the music to flow in and out of the film space as the story progresses. The film is candy for the eyes.

One scene that particularly stands out is the musical number, which features multiple actors and actresses singing about missing loved ones. Their faces appear like specters, illuminating a pitch-black background to show the sheer number of cartel violence victims as they exist in the darkness of despair and uncertainty. However, a film at this professional level should have good cinematography and editing. Other factors that make the movie experience authentic were missing.

Representation

In 2025, it shouldn’t be too much to ask to shoot a film about one of Mexico’s premiere public problems in actual Mexico. This also means hiring Mexican artists and consultants to make the film as authentic as possible. In November of last year, Mexican cinematographer and director Rodrigo Prieto spoke directly about this in an interview with Deadline:

“First of all, I’m unhappy that the film was not shot in Mexico. Secondly, why wouldn’t you include more Mexican people to participate in the production? Not even just as actors. We do have Adriana Paz in the film and she’s great. I think she’s great. It was a breath of fresh air when I saw her in the movie. She feels Mexican to me in an authentic way. Everything else in the movie feels inauthentic and it really bugs me. Especially when the subject matter is so important to us Mexicans. It’s also a very sensitive subject. The whole thing is completely inauthentic. I’m not talking about the musical side of it, which I think is great. That’s a great idea. But why not hire a Mexican production designer, costume designer, or at least some consultants? Yes, they had dialogue coaches but I was offended that such a story was portrayed in a way that felt so inauthentic. It was just the details for me. You would never have a jail sign that read ‘Cárcel’ it would be ‘Penitenciaria’. It’s just the details, and that shows me that nobody that knew was involved. And it didn’t even matter. That was very troubling to me.

I’m not against non-Mexicans making films in Mexico but the details are important. Look at Ang Lee. He’s from Taiwan and made Brokeback Mountain. But he focuses on the details. Even me with Pedro Páramo. I’m not from the Mexican countryside but I went and spoke with people to learn how best to depict the culture. It’s about the details.”

To add insult to injury, the film’s director was a bit flippant about the preparation for the film:

It is crucial to handle this precious cargo with care. Cartel violence and its overall impact on the degradation of Mexico’s civic system is a deep issue for the world, particularly for Mexican citizens. It’s crucial to get the details right and be sensitive to them.

Adding to the inferno is this statement from the Gay and Lesbian Alliance Against Defamation (GLAAD):

“Now that ‘Emilia Pérez’ is streaming on Netflix, more people are able to critique this profoundly retrograde portrayal of a trans woman.

While the film garnered rave reviews when it premiered at Cannes earlier this year, none of those reviews were written by trans people. There is an ongoing challenge with high-profile film festivals programming films about trans people – which are then seen and reviewed by cisgender critics – months before an actual transgender person can even see the film.”

Visiting GLAAD’s page is highly recommended as the organization compiles numerous reviews by trans critics who express dissatisfaction with the portrayal of trans identity. One review by Amelia Hansford at PinkNews wrote in “Emilia Perez is a Bad Film”:

“Emilia Pérez’s screenplay is so cisgender it’s almost satirical. In fact, its the single biggest indicator of Audiard’s gender identity. He might as well have the word “cis” tattooed on his forehead. What’s immediately frustrating is that Emilia Pérez exudes a kind of confidence that’s almost nauseatingly sure of itself when it shouldn’t be. For example, lumping breast augmentation and nose jobs in with bottom surgery, or having Castro physically recoil at the effects that hormones have had on Pérez’s body, or when Emilia’s daughter says she smells “like a man.” It’s a script that is so alienated from the process of transitioning as a trans woman – and yet blurts falsehoods out with such bold, intense conviction – that you’d think Audiard himself had gone through 500 different gender-affirming surgeries in one sitting.

Emilia Pérez is primarily a film about being reborn, and it tries to use the idea of transitioning to convey that through her transition, Emilia is trying to repent for the sins she committed in her time as cartel boss. The issue with this is that transition isn’t a moral decision, and the act of transitioning alone doesn’t somehow absolve you of your past self. It isn’t a death, nor is it a rebirth. Instead, Emilia continues to use contacts from the cartel, manipulates her family into trusting and spending time with her, becomes physically aggressive near the film’s ending when reconnecting doesn’t pan out, and even opts to threaten her wife, played by Selena Gomez, with financial blackmail. one of this is framed in a way that makes any thematic sense and ends up showcasing Emilia as yet another psychopathic trans character to add to the pile.”

Drew Barnett Gregory of Autostraddler writes:

“Whether made by us or about us, I want more trans stories that are audacious, ambitious, and new. The problem with Emilia Pérez is that while it’s new in some ways it’s very, very tired in others.

The film hits just about every trans trope you can imagine:

Trans woman killer

Tragic trans woman

Trans woman abandons her wife and children to transition

Transition treated as a death

Deadnaming and misgendering at pivotal moments

Trans woman described as half male/half female”

A movie that was centered around a marginalized group has insensitively portrayed that marginalized group. Doesn’t sound like mission accomplished.

To make matters worse…

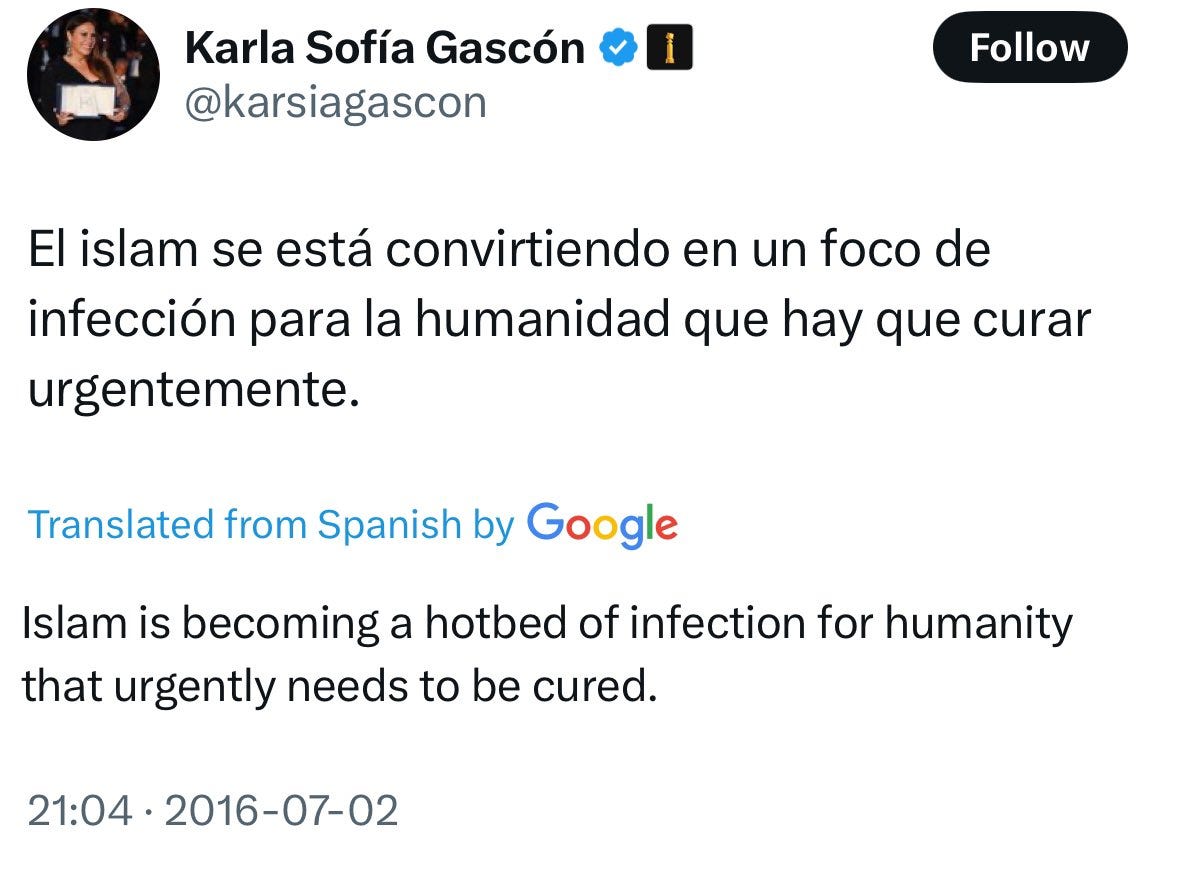

Everything presented above is enough to create a public relations nightmare. But the oxygen has been consumed by the revelations of the starring role’s Twitter page. Sarah Hagi is a culture critic who dug up some of her own bodies. She shared screenshots of some of Karla Sofía Gascón’s former tweets:

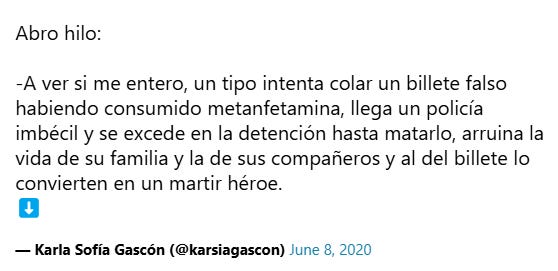

She also wrote a thread about George Floyd:

English Translation: “Let's see if I find out, a guy tries to sneak a counterfeit bill having consumed methamphetamine, an idiot police officer arrives and goes too far in arresting him to the point of killing him, ruining the life of his family and his colleagues, and they turn the guy with the bill into a martyr hero.”

She tweeted about the 2021 Oscars, calling it an “Afro-Korean festival” and a “Black Lives Matter demonstration.”

Another past tweet stated, “Chinese vaccine, apart from the mandatory chip, comes with a cat that moves its hand, 2 plastic flowers, a pop-up lantern, 3 telephone lines and one euro for your first controlled purchase.”

So this is where we are at.

After a month of fluctuating between apology and indignation, Gascón has agreed to stay silent as the marketing operation systematically erases her from the tour and some outfacing materials.

It’s that time of year.

In “‘Emilia Pérez’ and the New Era of Online Oscar Scandals,” Kyle Buchanan of The New York Times (not always the best source) writes about the specific types of scandals in this contemporary age:

It’s the latest and most striking example of a trend that became turbocharged this year in which awards strategists who used to influence the race with targeted whisper campaigns have been caught flat-footed by controversies that originate online and quickly get out of hand. Now, Oscar season has become a decentralized free-for-all where social-media sleuths and determined fan armies dig up past gaffes, bad tweets and damaging clips, then amplify them on X, TikTok and awards-adjacent subreddits.

That’s why, in the weeks leading up to the Oscar nominations, “The Brutalist” was pilloried on social media for using an A.I. speech tool to perfect the Hungarian spoken by star Adrien Brody, while “Anora” came under fire for failing to employ an intimacy coordinator. The ascendance of Brazilian best-actress nominee Fernanda Torres further boosted the bedlam, as her fan base on social media went after Gascón for implying that people associated with Torres were “tearing me and ‘Emilia Pérez’ down.” Days later, it was Torres who had to apologize when online Oscar obsessives resurfaced a 2008 clip of her performing in blackface on a Brazilian comedy show.

Not all of these social-media controversies make their way to the very offline world that most Oscar voters tend to inhabit. In the past, contenders like “Green Book” and “Three Billboards Outside Ebbing, Missouri” faced online opprobrium for their handling of racial issues and still won multiple Oscars. And though “Emilia Pérez” had been lambasted online since last year for its indelicate staging of trans issues and Mexican culture, very little of that had been on the radar of Oscar voters, who largely consider the movie to be bold and progressive.

He continues to predict the impact of this trend while recording his interview with the film’s lead:

No matter the ultimate outcome, this controversy will surely change the way awards campaigns are waged going forward. Many in the industry were surprised that Netflix strategists and Gascón’s own publicists had failed to persuade her to scrub her old social-media posts before the Oscar bid exposed her to a new level of global scrutiny. You can expect that sort of across-the-board purge to be a campaign mainstay in the future.

In the meantime, Oscar strategists will have to account for their own blind spots. One hopes Gascón eventually will, too. When I interviewed her last August, those blind spots came up as she spoke passionately about the case of the Olympic boxer Imane Khelif, whose eligibility had been questioned by the likes of J.K. Rowling, the “Harry Potter” author.

“It’s always the same story of these same people trying to find a new victim to generate more hate,” Gascón said. “It’s a constant element in human history. Before, it was people of color or women or workers. Now, it’s trans people.”

Her voice rose. “And even me, maybe without even knowing it, I have some prejudice or I criticize some communities because we all do it,” Gascón said.

It’s an understatement to state that we are living in sensitive times. Trans people are being silenced and put in danger by revanchist, health-illiterate policies. Mexicans are being scapegoated as criminals and moochers while the conversation around root causes gets lost in a fog of racism and anti-intellectualism. People need art to tell real stories and not cater to a careless sense of representation that feels more like a ploy to mine Oscar gold. I hope that is not the motivation and that these are just missteps. Still, the hatred of marginalized communities is so potent in this contemporary moment that it is easy to assume the worst, especially as a marginalized person faced with microaggressions in both our civic spaces and our creative spaces.