Walt Disney Presents Nostalgia

A reflection on the first episode of the 1950s Disneyland anthology series.

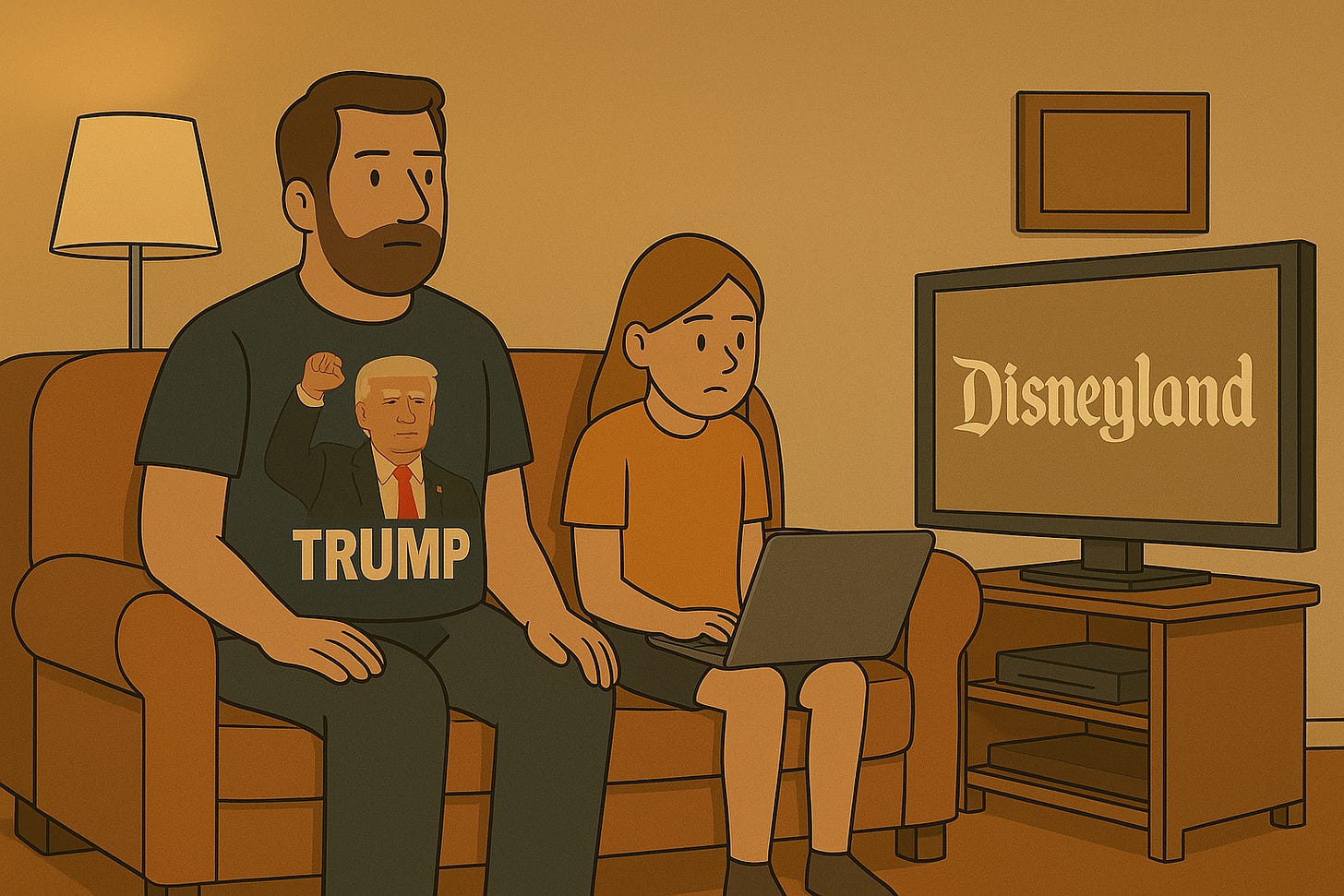

American Nostalgia

While taking a long walk, I began thinking about something I could never truly feel or experience:

What was it like for parents who grew up in the 1930s to share their Disney nostalgia with their kids in the 1950s? Was it filtered through a lens of remembering scarcity, yet shaded by the affirmation of rising postwar prosperity?

It’s a strange and nerdy thing to ponder.

But it speaks to the heart of cultural memory, intergenerational communication, and the increasingly fragmented American narrative. So I tried to imagine myself as a kid in the 1950s, and watched the very first episode of Disneyland, which aired on October 27, 1954.

The show was created as a ploy to get funding for Walt’s new passion project: a sanitized and orderly theme park that offered escape from the outside world, unlike the chaotic, dusty amusement parks that already existed. To fund the endeavor, Disney pitched television partnerships to the big three networks: ABC, NBC, and CBS. CBS wanted the show in color, which annoyed Walt, only because he thought their method was not up to his standard. NBC, owned by RCA, saw the show as a chance to sell more TV sets. Roy Disney even contemplated a merger with RCA, but when executives dragged their feet, the Disney brothers turned to the smallest of the three: ABC.1 Thus began the historic partnership between Disney and the network that was hungry enough to believe in Walt’s vision.

Rewatching this first episode provides a lens into an America that remains embedded in the imaginations and political ethics of a critical mass of its citizens. That’s not necessarily a bad thing—it’s a very human thing.

The Episode Itself

This 1954 premiere followed earlier Disney holiday specials that had paired classic shorts with a cozy, Midwestern tone. They revealed that Walt Disney, while no Roosevelt, was reviving the fireside chat tradition—this time with dreams and myth, not shortages and war. All in all, nostalgia wasn’t just part of the Disney brand; it was the lifeblood of the Magic Kingdom.

In the premiere, Walt introduces the concept of his theme park, which would be opening the following year, to those who could afford it. He offers viewers a behind-the-scenes look at the Disney studio in real time, including production on 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea (released months after this episode aired) and animation tests for Sleeping Beauty, which wouldn’t be released for another five years.

Later, Walt’s team teases the upcoming Davy Crockett series as part of the Frontierland offering. This, like much of 1950s Western storytelling, flattened American history into a tale of heroic White pioneers braving a wilderness populated by caricatured Indigenous "savages." It wasn’t unique to Disney—it was the dominant cultural narrative—but Disney had the reach to make it gospel.

The Adventureland segment follows with globe-trotting footage from Disney film crews, capturing wildlife and “unusual people from faraway places.” These scenes were technically impressive but culturally troubling, often mythologizing the communities on screen through stereotypes.

One scene transports us to a gathering in Algeria—a country that, at that very moment in 1954, was embarking on a bloody war for independence from France. But you’d never know that from Disney’s lens. Instead, Algeria is presented as timeless and pre-modern, with no hint of its urban life, political unrest, or cultural complexity. This, too, is part of the Disney imagination: to transform geopolitical complexity into spectacle, always at a safe emotional distance.

Tomorrowland offers a refreshing shift, even by modern standards. While it oversimplifies space science, it captures the sincere awe and curiosity Americans felt about the cosmos. It’s easy to see how a kid in 1954 would’ve been glued to the screen.

But then comes the segment that still haunts: Song of the South. This film, Walt’s attempt at an “American fairy tale,” leaned heavily on romanticized depictions of plantation life. The portrayal of Uncle Remus has not only elicited adverse reactions from African Americans at the time of production2, but also continues to do so today. Disney’s adaptation reimagined the character of Remus not as the sharp-witted, storytelling trickster found in Joel Chandler Harris’s original tales, but as a flattened the figure as more of a minstrel, mammy, and magical Negro designed to soothe White audiences rather than reflect any lived Black experience.3

After this segment, Walt shifts back to Mickey Mouse. It’s a fitting pivot. For parents who had grown up in the 1930s, Mickey was a symbol of light in dark times. Now he is reborn for a generation where the critical mass may never know want like previous ones. Walt shows the 1928 short "Plane Crazy" and then clips from "The Pointer" (1939), where Mickey teaches Pluto how to be a hunting dog before being chased by a bear. The evolution of Mickey is clear—not just in animation, but in his emotional tone, his polish, and his place in American memory.

By 1954, Mickey was no longer just a cartoon; he was a bridge between generations.

The Nostalgia Machine

My curiosity about 1950s parents watching their children embrace Disney was rooted in something more profound: my fascination with nostalgia as a central feature of the American story.

Nostalgia is powerful. It can help us remember, honor, and even heal. However, it can also be weaponized to deny the present, dismantle progress, and anchor us to a version of the past that never truly existed.

This first Disneyland episode is soaked in midcentury myths: about race, about empire, about the West. It infantilizes African nations and Black Americans, whitewashes the violence of westward expansion, and presents modern geopolitical realities as quaint curiosities. But this is the cultural scaffolding that shaped a generation. These narratives didn’t stop in 1954—they became the emotional fuel behind the backlash to the rights revolutions of the 1960s and 70s, and the flashpoints we still see today.

Disney sold not just a sanitized version of America, but a deeply comforting one—technically dazzling, narratively safe, and psychologically soothing. For parents of the 1950s, that comfort was redemptive. They had survived the Depression and a world war. Now, through television and eventually Disneyland, they could offer their kids a world built not on struggle, but on promise.

Today, nostalgia takes on a different form. It’s no longer about deprivation, but about the loss of identity—about a perceived unraveling of national innocence. The Disneyland episode, and the cultural machinery behind it, still hums in the minds of those who long for “simpler times.” Theme park rides, historical rewrites, and revised standards of inclusion have become battlegrounds. And so we face a darker nostalgia, not the kind that heals, but the kind that calcifies, and potentially, the kind that cripples a superpower.

Cotter, Bill. 1997. The Wonderful World of Disney Television: A Complete History. New York: Hyperion.

As Peggy Russo details in Uncle Walt’s Uncle Remus: Disney’s Distortion of Harris’s Hero, the Black actor Clarence Muse was originally brought on to help write the script for Song of the South and advocated for a version that would uplift Black cultural representation. However, his suggestions were rejected by Disney, prompting him to resign from the project.

Russo argues that Disney’s Uncle Remus became a composite stereotype—“part minstrel, part mammy, part magical Negro”—that flattened the character into a harmless, servile figure designed to soothe white audiences. This marked a significant departure from Harris’s more complex and ironic portrayal in the original folktales. See Peggy Russo, Uncle Walt’s Uncle Remus: Disney’s Distortion of Harris’s Hero, Southern Cultures, vol. 8, no. 4, 2002.

The role Disney and Disneyland played in the culture is fascinating…Disneyland did what you said—sanitized everything, became a kind of propaganda of the future and the past—and more. It created a kind of pretense of rational order and indulged in vast oceans of racism and orientalism—but strangely, perhaps it was not exactly the kind that current fascists want. They want hate, they want direct enemies whom it is permissible to crush, they don’t want people to dream about other lands, or believe science will bring every possible solution, or have a friendly if horrifically condescending and false view of other people and cultures. Even the lies about history are too much for people who want to erase history. Maybe there are different versions of white supremacy because the current trend is about a struggle which white people could lose, and they want everyone stomped out, or much more subordinated in a manner that cannot fit into the Disney worldview. The Disney worldview is largely secular and hopeful, for example. It’s much more amenable to democracy, and it has an internationalist flavor even if that involves imperialism and colonialism.

There’s something ahistorical about the current rightwing even as they constantly pretend to be drawing on history and try to generate nostalgic desires to arrive at the past. They are threatened even of false depictions of the past perhaps because the past they yearn for is unlike anything that ever was, and this can become clear even when you look at something like Disney.

Then when Disney started to moderately adapt to cultural shifts, and made room for certain realities they went absolutely bananas. It drove them crazier than almost any other cultural product. It was so fascinating to see them turn against icons of American ideology like that. Maybe it’s just their fear and suspicion is so intense that the very weight of cultural influence something like Disney could have is innately a threat even if it is posed to support the status quo as much as possible—because the cultural norms it would enforce don’t go very well with the norms the American right prefers—but maybe they never did.

Almost 80, I have memories of watching Disneyland every week on TV. Not having access to a color TV until I was out on my own post grad and able to afford one, the Disneyland of my childhood was always in monochrome.