In Dayton, Tennessee a trial emerged in the mid-1920s that featured an older conception of parents' rights which reverberates into today. An era of rapid change unmoored those who saw themselves in a more traditional light. “The Scopes Monkey Trial,” as columnist H.L. Mencken called it, offers a framework for the different factions forming in modern America based on region, gender, ethnicity, and generation. Clarence Darrow’s trials of the 1920s are the other side of the “Jazz Age” and display a nation setting the pace for future disputes.

Born in One Age, Growing Old in Another

In 1857, the sleepy town of Kinsman, Ohio had only been half a century removed from being western forest surveyed by Easterners from the newly minted United States of America. The Kinsman Township is named after John Kinsman who surveyed the land far back as 1799. However, by the 1850s, the “Northwest Territory” had been thoroughly settled by Americans, which also meant pushing Native Americans further west or forcing them onto reservations and into brutal assimilation measures. Thanks to a “Market Revolution” during the 1820s and 30s, spurred by newly built canals and steam-powered boats on the Mississippi River, Ohio was becoming a hub of trade and manufacturing. Though Darrow was born in the waning days of the antebellum Midwest, he came of age in a tumultuous period that saw the Old Northwest (and the nation) achieve immense wealth and production power on top of staggering inequality.

Eventually, Darrow ventured from Ohio to Chicago to become a big-city lawyer that worked for railroad companies as well as political machines and labor organizations. He originally rose to prominence through turn-of-the-century Democratic politics in Chicago. The industrial wealth that was amassing (especially in what was becoming the modern Middle West) didn’t include the laborers who made the manufacturing and extraction operations possible. The calls for economic justice and labor reforms opened a door for the Democratic party as it slowly transformed from a rump regional cabal into a national operation favoring common concerns and laborers. Darrow gave speeches that enticed local interests and showcased his abilities. But eventually, Darrow worked as a lawyer for the Chicago and North-Western Railway Company until he took a financial loss when choosing to represent prominent socialist Eugene Debs in 1894, also the leader of the American Railway Union. He helped Debs avoid prison in the first trial.

At this point, Darrow was known as a prominent labor lawyer and handled cases for the AFL, United Mine Workers Union, and Western Federation of Miners. Darrow was an anti-imperialist and opposed U.S. policy in the Philippines.

This life would continue into the second decade of the 20th century until a trial over a bomb placed by the McNamara brothers (J.J. and J.B.). The violence was over an open store dispute that incentivized the brothers to plant a bomb at the Los Angeles Times, which exploded and caused a fire to break out in surrounding parts of Los Angeles. The year was 1911, and a 54-year-old Darrow was working on a plea deal for he likely sensed the case was sinking. Though, the notorious labor lawyer was caught trying to bribe a juror, or having knowledge of the bribe, and eventually faced his own scandal. The first one ended in a hung jury, but Darrow avoided more legal action by promising to never practice in California again. The man was known as a skilled trial lawyer that could manipulate juries with his intellect as he ended up defending himself in one of the bribery suits.

From this point on, Darrow was toxic for labor unions. So, he changed over to criminal and civil law, bringing us to the 1920s.

An Age of Spectacle

The 1920s saw America enter an age of celebrity, mass media, and technological wonder. People flocked to budding metropolises that seemed to be electrifying overnight. This wasn’t just in terms of new lighting (as electricity became more widespread yet still a relative luxury) but also in the eclectic art scene, the growing abundance of diverse populations, and the demonstrations of modern life and technology that cities had to offer. The gleaming cities of the turn-of-the-century Midwest were a much different place than the world Clarence Darrow grew up in.

Still, the progressive Darrow was time enough for it. He was the product of a father who was an ardent abolitionist and an early supporter of women’s suffrage. Remember, Darrow chose to defend a labor leader over his safe job at a Chicago railroad. The seemingly unsuspecting trial lawyer was molding into a prop of history as times changed with his approval and advocacy.

Another factor that aided Darrow was his ability to play the country lawyer that featured an undercover intellect which took jurors and his detractors off guard. In an era where trials were becoming highly publicized with photographs and audio recordings, this was a crucial aspect in adding a sense of down-home flavor to the legal spectacles to come.

Three trials in the 1920s demonstrate Darrow’s philosophical beliefs and historical positioning as America entered a truly modern moment. The first trial features the murder of Bobby Franks (a 14-year-old boy) by late-stage teenagers Nathan Leopold Jr. and Richard Loeb. The boys pleaded guilty after intense interrogation as police didn’t have to read them their rights upon arrest. Still, the wealthy guardians of the boys hired top-notch lawyers, including Darrow. The best outcome was life in prison and avoidance of the death penalty.

The former labor leader's credentials as a representative of the underdog were put under scrutiny with accusations of defending the boys just for money. But he insisted this was part of his overall advocacy against capital punishment. After a lengthy statement from the families of the defendants, the Chicago Bar Association had officers form a committee to determine the legal fees for Darrow and accompanying lawyers. It is estimated Darrow kept $30,000 from his defense after taxes and expenses. ($375,000 in 20161). It needs to be noted that despite the admitted guilt of the defending parties, there was also an immense amount of anti-Semitism influencing the public climate as Leopold and Loeb were both from wealthy Jewish backgrounds. The Protocols of the Elders of Zion animated the anti-Semitic sentiments of many a Gentile.

The case was dubbed “the Trial of the Century” by the popular press and added to an overall conversation about wealth and the criminal justice system. The 18 and 19-year-old were sentenced to 99 years in prison but avoided the death penalty. Darrow argued the boys were emotionally unstable and could not be held responsible for their actions due to not being able to feel revulsion. Darrow’s insanity defense was published around the nation in the 1920s and 30s as well as coalescing with his theories on crime and punishment. For Darrow believed capital punishment was immoral in regard to his other belief that free will did not exist and that people were powerless in the face of their genetics, specifically their endocrine glands.

It should also be noted that Darrow was an ardent opponent of the eugenics movement, which he regarded as a cult.

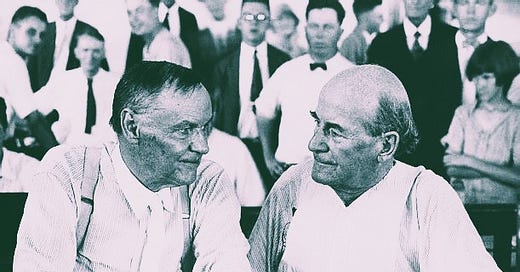

The second trial is the most famous and centered around a teacher in Tennesse teaching Darwin’s theories on natural evolution. Darrow defended the teacher of Darwin’s theories, John T. Scopes, in a highly publicized trial that pitted biblical creationism against the theories of natural evolution. This court proceeding famously featured Darrow calling his legal opposition, perennial presidential election loser William Jennings Bryant, to the stand as an expert witness on the Bible. Bryant admitted that some aspects of the Bible could only be interpreted as metaphor.

Still, this questioning was cut short by the judge and expunged from the record.

The science teacher was found guilty and fined $100 for violating the Butler Act, which was a Tennessee state law that prohibited the teaching of evolution in public schools.

Sound familiar?

The state’s supreme court reversed the decision on a procedural technicality but instead of taking further action, they dismissed the case.

“Nothing is to be gained by prolonging the life of this bizarre case.”

-Tennessee Supreme Court

The third case is that of Ossian Sweet, who was a Black man that moved his family to a White neighborhood and was attacked by a White mob as a signal to Sweet to stop being uppity and thinking he and his family could live amongst White Americans. One White man died, and eleven Black men were arrested and charged with murder. Ossian Sweet was a doctor who had attended Howard University in Washington, D.C during the Red Summer of 1919 when White Americans in military uniforms pulled Black people from streetcars to enact violence upon them. He and three of his family members were brought to trial and were defended by Clarence Darrow.

The folksy lawyer argued that the case was pure prejudice and that if the roles were reversed, the White men would have been viewed as protecting their homes and standing their ground against a mob.

Sound familiar?

Darrow also argued, “They would have been given medals instead…”

Clarence was in the mold of his abolitionist father. He was an avid fan of John Brown and supported interracial relationships, racial justice, as well as being progressive on women’s issues. Darrow defended Sweet’s brother after the original case faced a mistrial that caused each individual to have to go to court separately. After Darrow successfully argued Henry Sweet was not guilty but acting in self-defense (Henry admitted he fired a gun), the other defendant’s cases were also dropped by the prosecution.

Darrow’s closing statement lasted seven hours and was publicized as a watershed moment in the legal history of the ongoing civil rights movement in America.

These three cases were the some of the last ones of Darrow’s career.

In 1932, Darrow would defend family friends in another racially charged trial that featured accusations towards a Native Hawaiian accused of raping and beating the wife of Thomas Massie, Thalia Massie, who was also the daughter of Grace Fortescue (both Thomas and Grace were defendants). Joseph Kahahawai’s case ended in a hung jury with charges being dropped and further investigations suggesting innocence. Still, in a froth of rage Massie and Fortescue successfully conspired to murder Kahahawai with the goal of forcing a confession. They were caught by the police immediately after committing the act (as they were transporting Kahahawai’s dead body).

It should be noted that Darrow was financially struggling throughout his life and was especially hit hard by the Great Depression at this point.

But he agreed to take on the case, with Massie and Fortescue being found guilty of manslaughter and not homicide. Darrow’s final arguments were transmitted through radio signals from Hawaii to the continental U.S. causing a larger discussion in White America about the credibility of the honor killing defense.

Clarence Darrow died in 1938 at the age of 80 in Chicago.

Understanding crime, racial prejudice, and religious extremism are still currents of American life and is weaponized by a revanchist Republican party.

Not all Americans progress in their thoughts and philosophy like Darrow. Education and exposure to other people and places is valuable and unfortunately not widespread. Darrow only stayed in college at Allegheny College for one year until the Panic of 1873 cut his time short. Still, he worked manual jobs and studied law on the side. Eventually, he earned his degree from University of Michigan’s law school and began his journey into the world of legal maneuvering and class politics.

Today, America still faces questions about racial identity, class differences in the form of inherited wealth, rising anti-Semitism, the necessity of capital punishment, and how to assess and rectify the roots of criminal behavior. These arguments and divisions don’t exist in a vacuum. The sooner we recognize the throughlines of our national pathologies, then the easier it will be to debate our differences and garner solutions to public problems.

The demagoguery coming out of today’s Republican party regarding Christian nationalism, white grievance/supremacy, and a revanchist push to make women barefoot and pregnant comes from a long line of Americans fighting modernity.

The decline of the GOP is a natural evolution of its prideful overlooking of the base motivations of many within their larger voting coalition. The elites are attached to history and philosophy yet still pridefully (and tragically) overlooked the deep-seated legacy of religious and racial bigotry in modern America. For many it was a blindspot as we are all prisoners to our own experiences, many times segregated ones due to natural and historical forces.

On the other hand, it’s irresponsible for people who know better to weaponize revanchist forces. But that is what happens when one rationalizes money and positioning as the ends of life rather than a clear conscience with a legacy of human rights to pass on.

Just because critics of the conservative movement focused on the elitism and a lack of compassion towards minorities doesn’t mean those same detractors didn’t understand and acknowledge the rational criticisms of overburdening bureaucracies and unaccountable spending. It means that many of the conservative movement’s critics knew (from personal experience) that the grassroots energy of the movement was based on a primal rage and discomfort with changing times.

This revanchist rebel yell goes back to the forces employing or opposing Clarence Darrow as his arguments paralleled national discussions undergirding a larger push and pull between America’s past and America’s present.

According to Wikipedia.