Imagine being drafted into the United States military at age 18 and sent to foreign lands with army fatigues, weapons, and a vague mission to secure democracy. Now imagine coming of age in the 1930s when storm clouds formed over world affairs as the possibility of massive war raged forward. (Unfortunately, it is similar to today.) The generation that would fight in the Second World War had parents who fought in the First World War, a dreadful affair marketed by politicians as a fight for democracy. The Silent Generation, as we call them, observed militant aggression rise in Europe and Asia through newsreels, newspaper headlines, and stories from returning travelers. People could not be sure of the survival of the small bits of democracy that existed then; it often seemed to be on its last leg.

Also, during the 1930s, labor movements surged as the laissez-faire consensus of American economics crumbled in the aftermath of the 1929 stock market crash. Rural Americans felt the economic strain in the 1920s, and it was now gripping densely populated areas as businesses shuttered and jobs vanished. This tumultuous environment paved the way for demagogues who exploited racial tensions and populist resentment towards the wealthy elite. With feelings of being forgotten permeating society, the Republican Party was politically decimated for a period, having leaned heavily into their pro-business policies that left little social safety. The Democratic Party’s coalition, initially comprised of urban political machines and Southern segregationists, would gradually incorporate Western farmers with Franklin D. Roosevelt, an American aristocrat soon to be labeled “a traitor to his class,” leading this powerful national coalition.

The dire circumstances of the era necessitated Roosevelt and his advisors to redefine Americans' relationship with public social safety and, in the process, realign the principles of democracy with the reality of a flourishing middle class. This administration's reforms manifested in the Social Security Act, which legislated old-age benefits, unemployment insurance, provisions for aid to dependent children, and federal grants to states for different health and welfare programs. He also signed the Wagner Act, which helped codify workers' right to self-organize into unions with their chosen representatives, bargain for their terms and conditions of employment, and participate in “industrial democracy.” A strong emphasis was also placed on helping people attain home ownership by promoting the Federal Housing Administration and the Home Owners’ Loan Corporation. These and many other policy changes are known to history as The New Deal.

These dramatic policy changes and evolving considerations for ordinary Americans were the environment that World War II veterans and Silent Generation Americans grew up in. The New Deal Revolution electrified rural communities and the political imaginations of generations of Americans who had toiled in a laissez-faire dystopia hoisted upon them by the excesses of individualism, class politics, and antidemocratic movements (primarily directed at ethnic minorities).

Growing up, my grandfather talked about FDR wistfully. He was born in 1923 and was 9 when the Second Roosevelt was elected. He was 21 and at war when “the Sphinx” passed away.

Still, idealizing any generation or period when studying history is never good. Howard Zinn wrote in The Progressive in August 2001:

I refuse to celebrate them as “the greatest generation” because in doing so, we are celebrating courage and sacrifice in the cause of war. And we are miseducating the young to believe that military heroism is the noblest form of heroism when it should be remembered only as the tragic accompaniment of horrendous policies driven by power and profit. Indeed, the current infatuation with World War II prepares us–innocently on the part of some, deliberately on the part of others–for more war, more military adventures, more attempts to emulate the military heroes of the past.

…

If there is to be a label “the greatest generation,” let us consider attaching it also to the men and women of the sixties: the black people who changed the South and educated the nation, the civilians and soldiers who opposed the war in Vietnam, the women who put sexual equality on the national agenda, the homosexuals who declared their humanity in defiance of deep prejudices, the disabled people who insisted that the government recognize the discrimination against them.

Despite the missteps that come from putting too much of a glow on historical periods and people, it is true that this era of America progressively prioritized a healthy public square and a thriving democracy after spending years of their lives in an impoverished, often violent, multi-year episode that culminated in an industrial war against foreign fascism and imperialism. The emphasis on democracy in such a drastic manner was unprecedented in the history of our country. Within the adult lives of Silent Generation Americans (a group perplexed by memories of the Interwar period), an unparalleled expansion of democracy ensued after a brutal upbringing.

That isn’t to say things were perfect. In mid-century America, economic and social democracy still had a negative connotation and many detractors. Cold War pressures and a need to compete with what we perceived as an equally powerful arch-nemesis propelled the nation to take civics seriously and simultaneously regress it into an age of fear.

But, even with all of these negative modifiers, it is hard not to consider the impact that the 1930s and ‘40s had on the imaginations of Americans who lived through it. They were shaken out of a status quo that caused them to prioritize democratic institutions and labor safety as well as take the ever-rising tide of fascism as a serious threat. From that shake-up, we received infrastructure for building the midcentury middle class that sent record numbers of baby boomers to higher education at a comparatively lower cost.

Jonathan V. Last of The Bulwark recently wrote about a cutting but grounded topic. He wondered if Trump was right about us as a society. Maybe our priorities are so out of whack that we are open season for the brand of circus demagoguery that undergirds the Trump appeal. We live in an America that has watched its voting rights, and labor relations become shells of themselves while people obsess over celebrity romances. We inhabit a nation that has witnessed public schools become resegregated due to de facto structures and social patterns that perpetuate racial hierarchies. Even the ideas that debunked segregation are under attack. In America, there are tons of misinformed and civically illiterate citizens in a nation that harbors intense wealth while also projecting its cultural excesses and military hegemony on numerous countries abroad. Reproductive rights were overturned by Supreme Court justices appointed by unpopularly elected presidents. The nation watched on live television as Trump supporters ransacked its Capitol building. Confederate flag wielders and Trump cultists are unfortunate parts of the modern Republican coalition. Yet, we are on deck to have a second presidential term for the man who orchestrated such attacks and still praises the perpetrators of the attacks to this day. Many of the nation’s storytellers are still afraid to call out a major political party for endorsing the attacks on democracy because it may highlight an uncomfortable reality about each other and our fellow compatriots's silent but dark motivations.

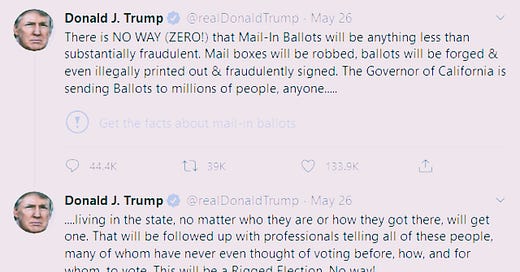

In an address that took place after January 6th, Trump refused to say the election is over even after the nation witnessed the outcome of his failed, months-long campaign to delegitimize the 2020 election results.

This past Memorial Day weekend, we remember those who have made the ultimate sacrifice to make American democracy a shining beacon. It may also serve as a time to assess how our society has developed. The generations of the past featured more bigotry than recent generations. Yet, we still have ghostly institutions of a racially divided past seeing a resurgence in American politics and intelligentsia. The idea of labor representation was a pipe dream during the smoggy Gilded Age, yet the structures put in place by past advocates are crumbling ever so quickly. A once thriving middle-class dream of affordable living and upward mobility now sees a generation potentially doing worse off than their predecessors.

If America continues to choose blissful ignorance over reckoning with a collective that has openly endorsed democracy’s doom, then maybe Trump is right about us.

Perhaps we are the spoiled successor generations of Americans who experienced the antidemocratic pains of the past and labored for their kids not to feel that same discomfort. Only to have those same kids grow up and squander that sacrifice in the face of extreme carelessness for civics, frivolous distractions aided by junk food media, and a lack of imagination regarding how bad it could be.

I sure hope not.

everyone needs to please stop overusing the word “imagine” and that whole framework. It is worse than “it is what it is.”