Unwieldy Coalitions

The liberal New Deal Coalition crumbles while giving rise to the modern, and increasingly illiberal, Conservative Coalition.

It was a bright and sunny spring day at the University of Maryland. I remember becoming enamored with the book Grand Expectations: The United States, 1945–1974 by James T. Patterson. As required reading for my undergraduate American history course, it deeply fascinated me. Not only because of my interest in mid-twentieth century America. But also because the level of detail in the book. The epic takes different historical events and puts it into a streamlined narrative. In a way, it’s a tragedy about a nation growing in extreme wealth and rights consciousness, but also hosting grand, and arguably, impractical expectations. The era the book covers is a world of expanding government programs. It’s an America with a growing middle class and a populace harboring a sense of infinite possibilities after a titanic global victory.

This expansive history is one of many volumes in the larger Oxford History of the United States. But even as the decades moved forward from the halcyon post-World War II days, a major throughline remains: the collapse of the liberal New Deal political coalition under the weight of grandiose expectations regarding our society's ability to solve problems that have plagued all of human history.

First, what is a coalition?

Merriam–Webster defines a coalition as “a temporary alliance of distinct parties, persons, or states for joint action.”

In parliamentary legislative structures, coalitions have many political parties. They come together to form a governing consensus. In America’s two-party legislative structure, a coalition of interests will come together under one party flag to win elections. From the 1930s to the late 1970s, the New Deal coalition was a collection of “distinct elements” that banded together under the Democratic Party. The result was more public spending after a period of sustained privatization. But the coalition also included foreign interventionists as the U.S. expanded it's global footprint time and again over the previous half century.

The postwar liberal consensus’ crystallization phase occurred during President Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s four presidential terms. Roosevelt introduced new additions to America’s wavering social safety net as well as led the nation through its largest and most dramatic foreign excursion (and spending project). His political followers consisted of Southern segregationists, labor advocates, military interventionists, and civil rights-oriented groups. This collection of interests came together to give the Democratic Party legislative power for much of the mid-twentieth century. Coincidentally, this period featured more labor reforms than Republican-led eras. This happened through new public programs and a progressive tax rate. Also, bipartisan civil rights legislation would define the political rise of Americans of color. However, Democrats will maintain a coalition with people of color, specifically African Americans, as Republicans work hard to court segregationists and pass policies that solidify its de facto elements (which reverberate into modern times).

But nothing lasts forever.

The end of the New Deal coalition coincides with disastrous foreign policy decisions. It also fractured due to differences in people’s opinions over civil rights reforms. In 1964, the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party (MFDP) challenged the seating of the Mississippi Democratic Party at the national convention in Atlantic City. The MFDP was meant to shed light on all-white primaries in Southern states and voter intimidation efforts directed towards Americans of color. The MFDP was viciously silenced by the national Democratic Party out of fears of a Dixiecrat (Southern Democrats) revolt. But, in return, the MFDP was offered two seats as a small recompense. More importantly, the reverberations of this uproar further cemented the tenacious voice of people of color within the Democratic Party - a population (along with all working Americans) that benefits from labor awareness, democratization, and modern social safety.

Patterson’s book begins as World War II is ending. President Harry Truman carries the mantle of international New Dealer. In this image, he must be an advocate of liberal democracy. But, diplomacy immediately breaks down with Soviet Russia and China becomes a Communist stronghold by 1949. Thus, growing political pressure from the right-wing of both parties, and paranoia within America, result in the creation of a massive defense bureaucracy. Soon, a second culturally-inclined Red Scare occurs and the GOP sees a political opportunity here. One of their plays is to claim Democrats are soft on communism, a tool that nonetheless gives rise to Joseph McCarthy and Richard Nixon. Thus, the period of the late-1940s and 1950s sow the seeds of the GOP's hawkish profile, even though their previous isolationist tendencies lie dormant.

Also during this tumultuous period, Democrats, specifically under LBJ’s “Great Society” policies, tried to supply both “guns and butter for the foreseeable future.”

Meaning, Democrats wanted to be the party that both won wars and gave Americans domestic benefits. That is expensive and an ill-advised war in Vietnam rained on that parade. The spending for the war and the spending at home ran the economy too hot. Despite a tax surcharge, rates still weren't high enough to meet the war’s spending demand. Thus, the American people plunged head first into an inflationary decade. To the American people, the New Deal policy order was unable to please larger national hopes. As Patterson points out, this is a period where Americans harbored grand expectations. Some of these expectations guided American leaders into waging wars against abstract and complex concepts. (For example, poverty, racism, the spread of nationalism, or drug use.) Maybe such lofty efforts and understandings of the world were bound to face national disappointment and dismay. That is a question the book plants into the reader’s mind.

Using history as a guide, its not surprising that the ashes of the mid-twentieth century liberal consensus would foster a new political force. One that would ascribe the problems of the present to a popular reliance on government.

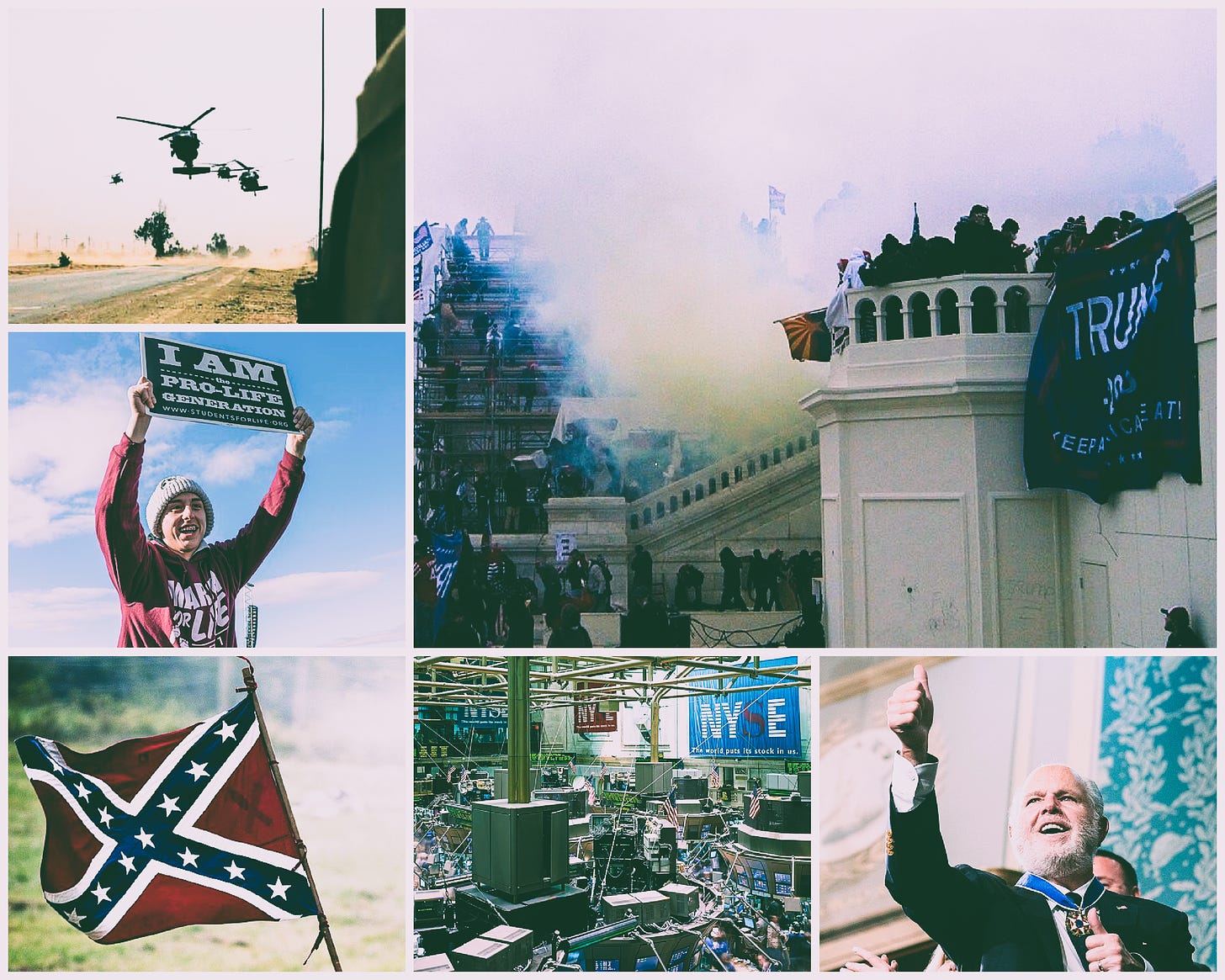

The aftermath of the liberal consensus saw a right-leaning political incentive structure that would find easy money by baiting the fears, racism, and greed of many Americans. It featured an agenda that defunded public spaces and deconstructed avenues leading to equal opportunity.

That new political force is the conservatism that defines the end of the 20th century and the current century. It has alienated generations who have grown up in its destructive wake. In some regards, the conservative movement did spur good faith intellectual vitality and authentic curiosity. But, too often was it energized by darker impulses. Out of hubris, or honest blind spots, conservative leaders were often ignoring or overlooking this darkness.

So, my next several posts will be around the idea of unwieldy coalitions. I will use this frame to unpack the modern conservative coalition by exploring different public problems. American politics ebbs and flows between an emphasis on uplifting the public square and an urge to retreat into private comfort. Usually this coincides with changing political alliances as generations come of age.

We may be living through the end of a coalition built by Goldwater and Nixon. The "Reagan Revolution” crystallized this coalition and national sea change and the "MAGA Movement" hardened it by tapping into a latent extremism. So it is worth exploring the evolution of the conservative coalition and how its role in our national life defines the America of today.