Naturalist, Astronomer, and Engineer

“The color of the skin is in no way connected with strength of the mind or intellectual powers.” –Benjamin Banneker

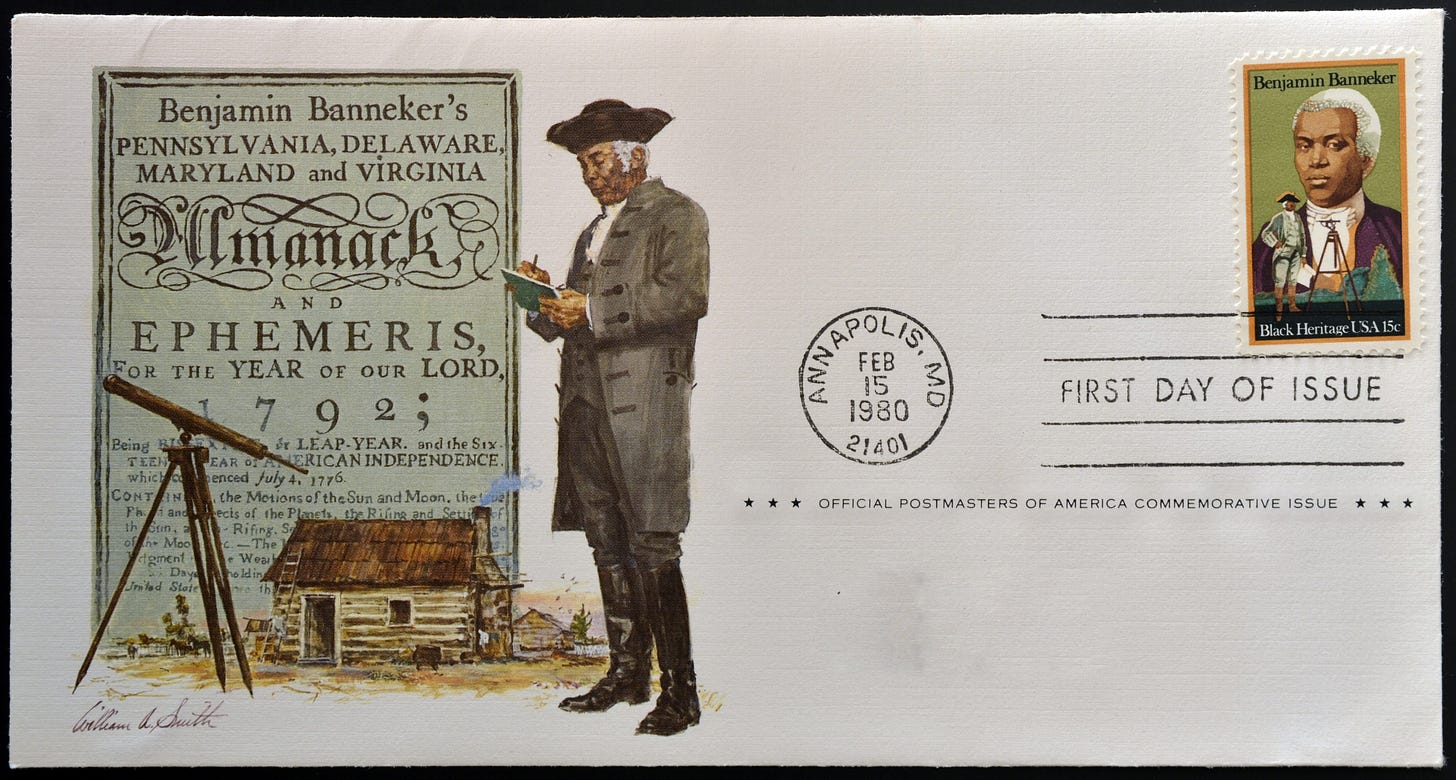

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA - CIRCA 1980: A stamp printed in usa dedicated to black heritage, shows Benjamin Banneker, circa 1980. Courtesy of Shutterstock and neftali

I learned about Benjamin Banneker when I was in the third grade. I was one of few minorities in my elementary school.

We still celebrated African American history and thankfully there was a deep sensitivity to it. Of course, being the fashionable young lad I was, I wanted to wear one of my football jerseys on dress-up day.

Students were able to come to the classroom dressed as their favorite African American figures from history on a select day in February.

There was a lot of Oprah in 2003.

My mother admirably wanted me to attend school dressed as Benjamin Banneker. She felt it was important to discuss people within the African American experience who are lesser known and who challenge stereotypes. That had an indelible impact on my understanding of history as existing with dual tracks.

There is popular history – which leaves out a lot of marginalized groups and local stories.

There is also a lot of revisionist history. Much of it seeks to uncover themes and contributions previously whitewashed by power structures and social animosity.

Unfortunately, a substantial amount of revisionism also seeks to do the opposite. The spread of a fabricated or a cynical view of the past is built out of aggressive nostalgia and contemporary discomfort.

Studying African Americans who have contributed to this nation in ways the popular story may not highlight is crucial.

It clarifies and humanizes these different tracks of history.

After all, that is the undergirding theme behind what Dr. W.E.B. Dubois defined as a “double consciousness” within the African American populace.

Obviously, this idea can apply to all other marginalized groups in this nation as well.

Benjamin Banneker’s story is one of freedom. Banneker’s father was an ex-slave and his mother, Mary Banneky, was the daughter of an Englishwomen who was an indentured servant. Banneky’s mother married a former slave who “asserted he came from tribal royalty in West Africa.” Benjamin Banneker spent most of his lifetime on the farm owned by Robert, his father, in Ellicott’s Mills, Maryland. He was a self-taught child but sometimes attended schools by abolitionists Quakers.

Avoiding the barriers of slavery also meant Benjamin had an inordinate opportunity to seek education – something that was elusive in the 18th century no matter one’s background. Benjamin Banneker was also extraordinarily gifted. He constructed an irrigation system for his family’s farm and he built a wooden clock that accurately tracked time for more than forty years until being destroyed in a fire. The clock earned him public attention.

As the Smithsonian Magazine puts it:

Banneker was 22 in 1753, writes PBS, and he’d “seen only two timepieces in his lifetime–a sundial and a pocket watch.” At the time, clocks weren’t common in the United States. Still, based on these two devices, PBS writes, ‘Banneker constructed a striking clock almost entirely out of wood, based on his own drawings and calculations. The clock continued to run until it was destroyed in a fire forty years later.’

This creation, which is believed to be the first clock built in America, made him famous, according to the Benjamin Banneker Memorial’s website. People traveled to see the clock, which was made entirely out of hand-carved wooden parts.

Banneker is also credited with producing an early American almanac in 1793. He was a gentleman farmer who evolved into an insightful naturalist as he spent time observing lunar and solar cycles. Banneker’s almanac also listed information about the tides, offered medical observations, and political commentary. In a copy sent to Thomas Jefferson, Banneker included a letter questioning Jefferson’s proclamations about liberty while holding slaves.

Read the full letter here.

Now Sir if this is founded in truth, I apprehend you will readily embrace every opportunity to eradicate that train of absurd and false ideas and oppinions which so generally prevails with respect to us, and that your Sentiments are concurrent with mine, which are that one universal Father hath given being to us all, and that he hath not only made us all of one flesh, but that he hath also without partiality afforded us all the Same Sensations, and endued us all with the same faculties, and that however variable we may be in Society or religion, however diversifyed in Situation or colour, we are all of the Same Family, and Stand in the Same relation to him.

…

Sir I freely and Chearfully acknowledge, that I am of the African race, and in that colour which is natural to them of the deepest dye,* and it is under a Sense of the most profound gratitude to the Supreme Ruler of the universe, that I now confess to you, that I am not under that State of tyrannical thraldom, and inhuman captivity, to which too many of my brethren are doomed; but that I have abundantly tasted of the fruition of those blessings which proceed from that free and unequalled liberty with which you are favoured and which I hope you will willingly allow you have received from the immediate hand of that Being, from whom proceedeth every good and perfect gift.

…

Sir, I suppose that your knowledge of the situation of my brethren is too extensive to need a recital here; neither shall I presume to prescribe methods by which they may be relieved; otherwise than by recommending to you and all others, to wean yourselves from these narrow prejudices which you have imbibed with respect to them, and as Job proposed to his friends “Put your Souls in their Souls stead,” thus shall your hearts be enlarged with kindness and benevolence toward them, and thus shall you need neither the direction of myself or others in what manner to proceed herein.

Thomas Jefferson was impressed by the observations and purportedly sought out Banneker to help survey the new federal capital in carved out lands to the south. Banneker apparently calibrated George Ellicott’s field clock during the survey using celestial movements. George Ellicott was a son of Andrew Ellicott and a prominent Quaker businessman. He lived in Ellicott Mills and is also credited for widening Banneker’s interest in astronomy.

The Ellicott family established Ellicott Mills, now Ellicott City, Maryland.

Banneker wrote to Jefferson about his work in the same letter:

This calculation, Sir, is the production of my arduous Study in this my advanced Stage of life; for having long had unbounded desires to become acquainted with the Secrets of nature, I have had to gratify my curiosity herein thro my own assiduous application to Astronomical Study, in which I need not to recount to you the many difficulties and disadvantages which I have had to encounter.

And altho I had almost declined to make my calculation for the ensuing year, in consequence of that time which I had allotted therefor being taking up at the Federal Territory by the request of Mr. Andrew Ellicott, yet finding myself under Several engagements to printers of this state to whom I had communicated my design, on my return to my place of residence, I industriously apply’d myself thereto, which I hope I have accomplished with correctness and accuracy, a copy of which I have taken the liberty to direct to you, and which I humbly request you will favourably receive, and altho you may have the opportunity of perusing it after its publication, yet I chose to send it to you in manuscript previous thereto, that thereby you might not only have an earlier inspection, but that you might also view it in my own hand writing.—And now Sir, I shall conclude and Subscribe my Self with the most profound respect your most Obedient humble Servant,

Benjamin Banneker"

Near and dear to Marylanders (and many others) is the experience of living with Brood X cicadas. They bring wonder and fear to people when they sprout from the earth’s surface every seventeen years. Benjamin Banneker is known as an early observer of this phenomenon.

Janet E. Barber and Asamoah Nkwanta studied Banneker’s journals and his writings on the topic:

The first great Locust year that I can Remember was 1749. I was then about Seventeen years of age when thousands of them came and was creeping up the trees and bushes, I then imagined they came to eat and destroy the fruit of the Earth, and would occation a famine in the land. I therefore began to kill and destroy them, but soon saw that my labor was in vain, therefore gave over my pretension. Again in the year 1766, which is Seventeen years after the first appearance, they made a Second, and appeared to me to be full as numerous as the first. I then, being about thirty-four years of age had more sense than to endeavor to destroy them, knowing they were not so pernicious to the fruit of the Earth as I did immagine they would be. Again in the year 1783 which was Seventeen years since their second appearance to me, they made their third; and they may be expected again in the year 1800, which is Seventeen years since their third appearance to me. So that if I may venture So to express it, their periodical return is Seventeen years, but they, like the Comets, make but a short stay with us–The female has a Sting in her tail as sharp and hard as a thorn, with which she perforates the branches of the trees, and in them holes lays eggs. The branch soon dies and fall, then the egg by some Occult cause immerges a great depth into the earth and there continues for the Space of Seventeen years as aforesaid.

Addressing “The Myth of Benjamin Banneker” in Good Faith

There is substantial backlash to the retellings of Benjamin Banneker.

Critics point out that historical sites and secondary sources “embellish” Banneker’s accomplishments. They debate that he constructed a clock by only being exposed to pocket watches. (As there were clockmakers in Annapolis and production stemming from the Northeast since before Banneker’s birth.) The same attempts to diminish Banneker occur in his writings about cicadas, which mirror other earlier writings. Criticism is also focused on his contributions to surveying the lands that became the Federal City.

Much of the critique comes from Silvio Bedini, writing during the rise of modern revisionism and a time of rising Black pride. He concludes there is scant documentation and evidence to suggest Banneker was a part of the commission, was appointed by President Washington, was recommended by Thomas Jefferson, and was reinterpreting a frustrated Pierre L’Enfant’s blueprints for members of the Ellicott family.

Many of these criticisms are rooted in Bedini’s works from the late 1960s and 1970s. However, criticisms have carried over into the present when challenging Banneker’s portrayal at Smithsonian museums.

Many of these critics conclude that if Banneker had a role in the surveying of Washington D.C., then it was brief. This happens while also acknowledging general uncertainty.

I am not debating that historiography played a role in the way Benjamin Banneker was told and retold - just like with Thomas Jefferson and George Washington.

But, modern historians who want to focus on this - without pointing out the way doctored historical narratives undergird a popular belief that African American’s contributions in America have been lacking – also come off as cherry picking out of one’s own pride, prejudice, and biases.

There is a way to call out embellishments while honoring the message.

As we live in a time where we get constant examples of hidden history designed to protect the fragile sense of superiority among many in preferred classes – we also must apply that same understanding when learning new things about African Americans in the collective history of the United States.

To this day, one of my fondest memories is my mother taking me to the Benjamin Banneker Historical Park and Museum.

As usual,this excellent writing delights me!Proud grandma I am!