March 21, 1556: Church and State

Thomas Cranmer is burned at the stake during Queen Mary I's backlash to the English Reformation.

Thomas Cranmer, the Archbishop of Canterbury.

Early to mid-16th-century England dealt with a monarch who wished to exert power over his state, as well as his own ability to indulge in lecherous and self-aggrandizing pursuits. The outcomes of Henry VIII’s reign would have a cataclysmic impact on the world as a religious can of worms traveled from continental Europe across the channel and into the British Isles. The culmination of such transformations is viewed in the life of Thomas Cranmer, who was burned at the stake on March 21, 1556, during the reign of Mary I for his writings about the Church of England.

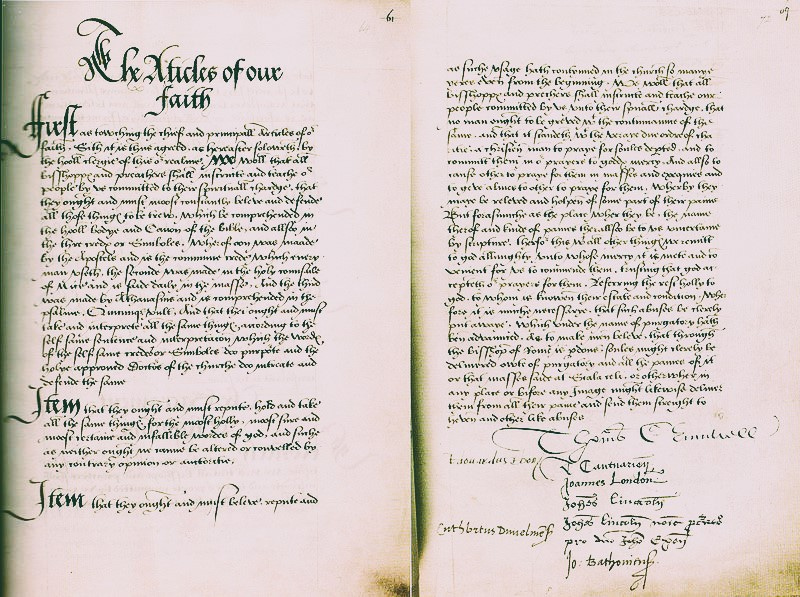

Cranmer was born in 1489 and came from a lower-gentry family that incentivized him to go into education (usually fostered by church-friendly institutions), as there was no land left for him to inherit. The future Archbishop of Canterbury would study at Cambridge at age 14 and threw himself further into his intellectual pursuits after his wife died in childbirth. He regained a fellowship at Jesus College he previously held and used it as a vehicle to enter church life in a more intense manner. By the 1520s, Cramner was part of a group referred to as “Little Germany” for they began to flirt with reform ideas coming out of Martin Luther’s revolt in a land that would become the German nation-state several centuries later. By the middle of that decade, Cranmer was calling for separation from Rome in his prayers. Though, he was still holding onto some papist beliefs quietly.

While staying in Essex to avoid “sweating sickness,” Cranmer was in proximity to the King’s delegation and that is where he meets the likes of Stephen Gardiner, who would evolve into a detractor. Moving forward, the King’s court saw Cranmer fitting for the production of a propaganda treatise that argued in favor of the King’s divorce from Katherine of Aragon. Katherine’s nephew was the Holy Roman Emperor, Charles V. So, obviously this upset the Roman Catholic establishment centralized in Rome, where Cranmer would eventually travel to defend his positions.

By now Gardiner’s sympathies to Rome pushed him out of Henry’s favor (something that happens often) and thus made Cramner, without being a bishop, the leading candidate for the role of Archbishop of Canterbury. He was the first protestant one. Thus, after the annulment is rejected by Pope Clement VII in 1533, Cranmer convenes a court at Dunstable and declares the original marriage void while pronouncing the marriage to Anne Boleyn, the king’s now pregnant mistress. Throughout the rest of Henry’s reign, Cranmer was a reliable and loyal arm to the throne even as his views shifted farther from the traditional-minded Protestants, whom King Henry VIII favored as the late stages of his administration began experiencing the chaotic consequences of his religious revolution. There were many in the Northern regions that still swayed Catholic, and within the budding protestant faith, there were schisms over Christ’s role in the Eucharist (transubstantiation) and the policy of compulsory celibacy among the clergy.

Cranmer turned against transubstantiation and publicly wrote about it which potentially put him in the crosshairs of Henry in the late 1830s with the Act of Six Articles, which codified into law the more traditional leanings. Still, Henry protected Cranmer until his death. Cranmer also held a unique ability to disagree with Henry and not be imprisoned for it. However, Henry had one son (Edward VI), and though his premature reign saw advances in the Church of England as Cranmer wrote prayer books and defined church dogma in the 1540s and early 1550s, his rule was shortlived and followed by a volatile backlash.

Queen Mary I is known to history as “Bloody Mary” for her morbid crackdown on Protestantism. Unfortunately, she probably pushed her personal traumas from being the daughter of Henry’s first wife onto her policy and populace. Cramner would be imprisoned and then put into comfortable entrapments only to be mentally tortured and made to publically renounce his writings, especially on transubstantiation. Though, Mary’s radicalized and off-the-rails court couldn’t hold back their blood lust and thus burned Cramner at the stake despite making the foremost intellectual of the Church of England publically defame himself in writing. Knowing this, Cranmer essentially said “fuck it” and renouncing his previous forced renunciations to the surprise of the Queen’s court and then went to die. This gave life to protestants hiding in fear and made a martyr out of this enigmatic, and often-disputed, Archbishop of Canterbury.

Religion is like Energy it's not created and it doesn’t die, it just moves on.

The larger Protestant Reformation sent shockwaves through a centuries-old Catholic establishment throughout Europe. It coincided with a budding era of monarchal consolidation and the beginnings of national entities defined by secular motivations. However, religion always exists in the background and the fragmentation of religious ideology would not only continue after the life of Thomas Cranmer but become an incubator for a civil war in England and induce further migration to a new world as people saw to recreate societies out of this religious fervor.

Here, in America, we see a lot of people claim to be Christian nationalists and even argue the framers of the American Constitution did not have the separation of church and state in mind. Ironically, here in Maryland, the old colonial city of St. Mary’’s is a living history area and the separation between church and state is seen in the blueprints of the town. The church and the statehouse were built on opposite sides of the town connected by a road to symbolize the two’s distinct and separate spheres. After all, this place is considered to be the birthplace of religious freedom in the United States as it was inhabited by protestants and Catholics, who could practice their traditions and coexist. The colony was settled in the 1630s.

It’s helpful to remember that religion can influence people the best versions of themselves, but can also be co-opted to produce ideological and sycophantic demons working towards power and not morality. We have this issue in America, where religious leaders will demagogue a populace into a violent anti-intellectual froth (and often adding a white supremacist dimension depending on the church) while using their donations to build mansions and water parks. This religious demagoguery is seen in all churches though, especially in Black churches.

We can avoid the fate of Europe during its religious wars, and realize thats one of the reasons America happened in the first place. We can use religion to bring people together and not divide them. Sunday shouldn’t be the most segregated day in America, and we can also acknowledge openly that Christian nationalist energy is the most anti-Christian energy.

Loved this. Tudor history is my area of greatest expertise so I read that avidly! Apropos subject. There was also a rabid anti-Howard/Boleyn faction that hated Cranmer with a passion. Mary truly blamed him for her parent’s marriage dissolution as well.