Rising Markets and Greedy Spirits

Gordon S. Wood’s Empire of Liberty gets gritty in its chapter on American society during the Age of Jefferson. This has been one of my favorite sections so far, not just for its substance but for the way it captures a country caught between dreams of liberty and the birth pangs of modern capitalism. For the first time, we truly see the on-the-ground consequences of democratization—and how the wealth class, or self-anointed aristocracy, recoiled at the very forces the Revolution had unleashed.

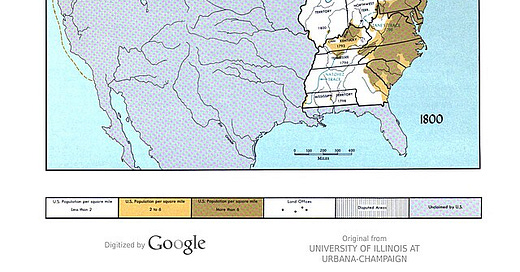

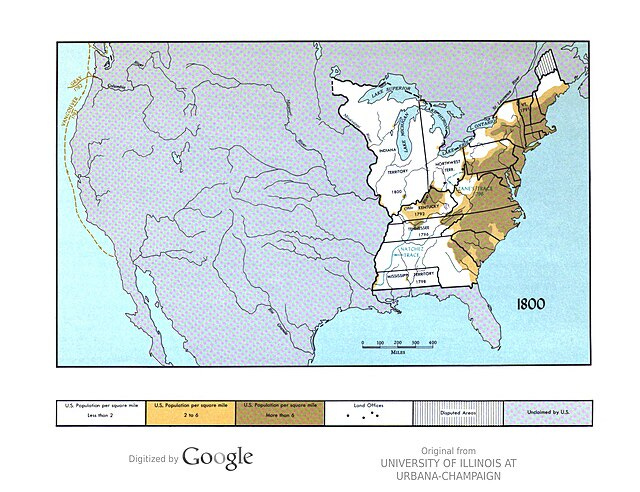

Even in these early days, when Kentucky and Ohio were still frontier states, a hunger for material comfort became a surprising catalyst for productivity. Eight years after joining the Union in 1792, Kentucky's population ballooned to 220,000. Wood notes that none of its residents had been born within the state. Migration was moving the nation westward—and so was ambition. By 1800, cities that would later define the Midwest, Pittsburgh, Cincinnati, Detroit, St. Louis, Lexington, Erie, Cleveland, and Louisville, had already been founded. Wood includes Nashville too. A restless public was laying the foundations of a new national economy, often far beyond the bounds of treaties and formal governance.

Wood argues that this energy wasn't just about survival. It was driven by desire—an aspiration to improve one’s standard of living through consumer comforts that once belonged only to the gentry:

“Farmers were becoming more productive because they glimpsed the prospect of improving their standard of living by consuming luxury goods that hitherto only the gentry had consumed—feather instead of straw mattresses, pewter instead of wooden bowls, and silk instead of cotton handkerchiefs.”

This democratization of comfort spooked the Federalist elite. To them, economic dynamism looked like social chaos. Americans, in their eyes, had become obsessed with commerce. Wood points to Boston-born and Harvard-educated Joseph Dennie, editor of The Port Folio, “the most distinguished Federalist publication in the age of Jefferson,” as a symbol of elite anxiety. Dennie decried democracy itself, warning that it had failed in Greece, Rome, England, and France. He predicted America would follow suit, ending in civil war and anarchy. For his screeds, Dennie was charged with sedition—though he was eventually acquitted.

But as Wood notes, the outcome was far less apocalyptic and far more familiar:

“Dennie and other Federalists soon came to realize that democracy in America was not going to end, as it had elsewhere, in anarchy leading to dictatorship and despotism. Instead, American democracy, driven by the most intense competitiveness, especially for the making of money, was going to end in orgies of getting and spending.”

The market economy hadn’t yet crystallized in the modern sense. But the building blocks were there—surpluses of production, long-distance trade with the Caribbean and Europe, and a growing detachment of the economy from older systems of social and cultural restraint. As Wood puts it:

“Only when the market became separated from the political, social, and cultural systems constraining it... only when most people in the society became involved in buying and selling and began to think in terms of bettering themselves economically—only then did Americans begin to enter a market economy.”

To explain how this shift took root, Wood draws on the work of economic historian Winifred Barr Rothenberg. Her research shows that even in New England, long before industrialization fully took hold, rural communities were already moving toward market-based thinking:

“In the 1780s and 1790s farmers were lending more money more often to ever more scattered and distant debtors and shifting more of their assets away from cattle and implements toward liquid and evanescent forms of wealth... By 1801... grain output in a sample of Massachusetts towns was nearly two and a half times what it had been in 1771... Only when these farmers increased their productivity to the point where they could support local manufacturing and consume its goods—only then could the takeoff into capitalistic expansion take place.”

Federalists, and many foreign observers, remained uneasy. The "mania for commerce and money" seemed like social disintegration. But in the North at least, many farmers and small businessmen embraced the competitive scramble. Wood notes that even within the Republican Party, this spirit of emulation, of keeping up with, and outpacing, the Joneses, became a potent force:

“Although most Federalists and even some Republican elites... were frightened by the growing mania for commerce and money... most of the farmers and businessmen themselves welcomed this competitive scramble. Some... used the Republican party to challenge the static Federalist establishment. Others sensed, as John Adams had, that competition arose out of the egalitarianism of the society... and they came to see that a spirit of emulation was good for prosperity.”

Modernity in its bones.

Reading this chapter is a reminder: modernity is in America’s DNA. The United States emerged alongside a rising industrial world and expanding global markets. Commercial activity was more than a tool of survival, it was the glue binding Americans to their dreams of freedom and prosperity. The market became the means of motion—westward, upward, outward.

The democratizing energy that powered the post-Revolution generation did not lead only to greater equality for some. It also ignited a culture of accumulation. And that “money mania” still echoes through American life. Sometimes, sadly, it feels like commerce is our only shared language, our only enduring ritual.

Making a buck became not just a means of survival but a marker of class and social worth. Even in this early moment, Americans were beginning to break away from a culture of deference, though elite forces still tried to maintain it. But that breakdown of deference didn’t just lead to opportunity, it also set the stage for something more volatile: a society where crudeness could be mistaken for authenticity, where unrest could spill into violence, and where ambition sometimes exploded into chaos. That darker undercurrent of riots, resentment, and raw energy will be explored next time.