January 6, 1942

President Franklin Delano Roosevelt speaks to Congress, and the American people, for a very special State of the Union address.

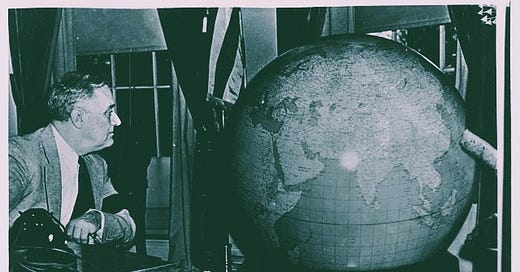

1942 - Franklin D. Roosevelt in Washington, D.C. via Wikimedia Commons.

The Four-Term President

President Franklin Delano Roosevelt (FDR) gave his ninth State of the Union (SOTU) address to the United States Congress. The patrician was elected for a third time in the fall of 1940 during a campaign that centered on stability and continuity in the face of international danger. This time, the New Deal programs were not the cornerstone of debate in this election cycle. Also helping was the reality that Roosevelt’s administration had overseen a generation now coming of age in the dust of economic calamity.

The older generation had their spirits broken by this sudden and shocking catastrophe.

With this trust, Roosevelt’s main mission was to defend the nation from storm clouds brewing over the Pacific and Atlantic Oceans. The president was already engaging in lend-lease with friendly governments like Great Britain, which would supply weapons to Allied causes all over the globe.

Also within this environment of change, FDR brought back (after a brief pause in the 1920s) the tradition his former boss and mentor, President Woodrow Wilson, had also revived.

For over 100 years, the presidential State of the Union address had been submitted in writing. It was delivered in person by Presidents George Washington and John Adams, but that was stopped by Adams’ political rival and successor, President Thomas Jefferson.

The speech would be delivered to Congress in writing until the 20th century.

President Coolidge gave one in-person speech, and President Hoover didn’t give an in-person State of the Union address. But FDR used them to his promotional advantage as his brain trust experimented with New Deal reforms. The Hyde Park Democrat even held a 1937 nighttime address in hopes of reaching a larger radio audience. This was also done by his predecessor when asking Congress for a declaration of war in 1917.

Finally, the 32nd president utilized aspects of the ongoing communications revolution, particularly radio, to bring the high office, and its initiatives, into the modest homes of everyday Americans.

The most famous of Rooseveltian messages were the “fireside chats.” His 1944 address would be submitted in writing, but was broadcast as one of these chats, usually on the radio and read by “the Sphinx.”

“We have not been stunned. We have not been terrified or confused.”

On January 6, 1942, President Franklin D. Roosevelt delivered the first SOTU address since the attack on Pearl Harbor. In this speech, Roosevelt outlines the complex plans for global supremacy prided by the Axis powers in a larger effort to connect the horrific December attack in the Pacific with the war clouds over Europe. Roosevelt explains how none of the recent events existed in a vacuum but how they also have awoken the sleeping American giant:

We shall not fight isolated wars—each Nation going its own way. These 26 Nations are united-not in spirit and determination alone, but in the broad conduct of the war in all its phases.

For the first time since the Japanese and the Fascists and the Nazis started along their blood-stained course of conquest they now face the fact that superior forces are assembling against them.”

He also emphasizes the role of America in the global conflict:

And so, in order to attain this overwhelming superiority the United States must build planes and tanks and guns and ships to the utmost limit of our national capacity. We have the ability and capacity to produce arms not only for our own forces, but also for the armies, navies, and air forces fighting on our side.

This speech is a culmination of years of Rooseveltian attempts to bring the federal government to the American people through promotional campaigns funneled through government programs hiring photographers:

Or through common participation in public programs:

Now the president was calling on the American people and its industries to produce a war machine:

First, to increase our production rate of airplanes so rapidly that in this year, 1942, we shall produce 60,000 planes, 10,000 more than the goal that we set a year and a half ago. This includes 45,000 combat planes- bombers, dive bombers, pursuit planes. The rate of increase will be maintained and continued so that next year, 1943, we shall produce 125,000 airplanes, including 100,000 combat planes.

…

And I rather hope that all these figures which I have given will become common knowledge in Germany and Japan.

…

Production for war is based on men and women—the human hands and brains which collectively we call Labor. Our workers stand ready to work long hours; to turn out more in a day's work; to keep the wheels turning and the fires burning twenty-four hours a day, and seven days a week.

Roosevelt was calling on his “friends,” the American people, to work long hours with hard sacrifices to aid the federation throughout this international challenge. Later in the speech he soberly brings up taxes and people giving up luxuries. (Not always a winner.) However, by now the Roosevelt administration had successfully cultivated a guardian-like persona and had become a commonplace voice of stability for Americans in this years-long period of uncertainty.

The call for more than a helping hand was positively received.

We must guard against divisions among ourselves and among all the other United Nations. We must be particularly vigilant against racial discrimination in any of its ugly forms. Hitler will try again to breed mistrust and suspicion between one individual and another, one group and another, one race and another, one Government and another. He will try to use the same technique of falsehood and rumor-mongering with which he divided France from Britain.

Franklin Roosevelt, State of the Union, January 6, 1942

Reflection

Once television appeared, President Harry S. Truman gave the first SOTU address on television in 1947. The age of television had dawned on the annual address.

Years later, and after the death of President John F. Kennedy, the speech became a primetime event at the behest of President Lyndon B. Johnson. By now television was coming of age. Also, these developments coincide with the continuous rise of the executive’s power and influence as another new communications medium supplied the branch with a tool to inform (or mislead and foment) the masses.

As America still reflects on the damage left by conniving and antidemocratic presidents, the nation must also grapple with the legacy of a branch that can have frightening levels of overt, and covert, influence in what is ideally the people’s government. A branch that can use its agenda-setting powers to spread any fiction that is dressed as fact through proxies in the media and radicalized true believers.

Talk Radio (1988)