Equality in Opportunity and in Education

Economic development is most meaningful when it uplifts the entire community.

(Articles and links work better if viewed through the web browser. Just click the article title in your email.)

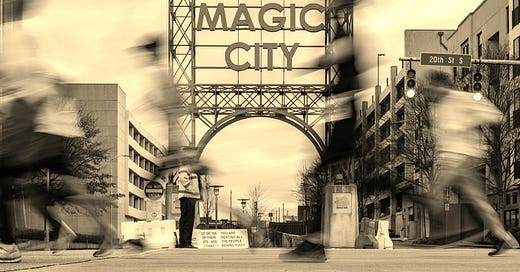

Birmingham, United States: February 16, 2020: Magic City Sign with Blurred Runners. Courtesy of Shutterstock.

America’s story is one of economic development. The tale is about an expansion that displaced and robbed marginalized peoples.

Though, it is also about the fight for democratization.

All over the United States of America.

A laissez faire corrupting force is enabled within the nation from time to time. It’s a force that threatens the health and well-being of our citizens and our environment. At the same time, it is intricately connected to the political corruption we experience.

In a more positive sense, this force can be understood and recalibrated towards developing ways to secure and revitalize our humanity and democratic spirit.

Transportation networks and industry recuperated a country reeling from a morbid civil war. It opened up the Western frontier - a place viewed as a hub for mythical renewal or fantastical escape.

It also liberated embattled communities in the southern states. Jim Crow laws spread throughout the land and they were reinforced by the Supreme Court ruling in Plessy v. Ferguson. Not only were communities of color facing legal segregation. The prejudicial environment also enabled systematic explosions of violence towards these communities. Law enforcement institutions often looked the other way.

Still, there were many who attempted to reform the regions they called home. For the economic transformations being made to the region challenged old orthodoxies and paved inroads towards a new future.

In Alabama, the number of operating factories rose from 2,000 to more than 5,500 between the years 1880 and 1900. Alabama had storehouses of iron ore, coal, and limestone to exploit as the economy steadily shifted towards industrialization. A highlight of this production boom was the rise of Birmingham, Alabama.

(In 1979, the city elected its first Black mayor, Richard Arrington Jr.)

The settlement grew so quickly it was nicknamed “Magic City” and also nicknamed the “Pittsburgh of the South” for its mining operations. After all, Birmingham is named after the city in England – also a major hub for that country’s iron industry among other parallels. Birmingham attracted the interests of Pratt Coal and The Tennessee Coal, Iron, and Railroad Company. The Louisville and Nashville Railroad offered special rates and facilitated growth as well.

U.S Steel bought interest within the city and completed a lock – and - dam system that gave manufacturers a cheap way to transport goods and materials. This fostered the city’s economic prosperity into the next century.

Despite economic gains in the post-Civil War South, there were numerous setbacks. This was experienced in the fight over the Blair Education Bill in the 1880s. The legislation was introduced in the U.S. Senate in 1880 by Republican Henry Blair of New Hampshire. It aimed to thwart illiteracy in the nation and was arguably the bookend to reform-minded legislation regarding the state of the postwar South.

Richard White explains the bill in 2007’s The Republic for Which It Stands:

The Blair Education Bill aimed to reduce the high rate of illiteracy in the United States, particularly in the South, and the failure to fund Southern common schools adequately. School spending provided one of the starker measures of the difference between North and South. In 1880 the sixteen former slave states spent roughly $12 million on education. The former free states appropriated more than five times as much. In North Carolina the state spent 87 cents per child. Only five states spent $2.00 or more per student to educate their children. Average northern spending per child ranged from a low of $4.65 in Wisconsin to $18.47 in Massachusetts, with only two other states spending below $5.00 per student. The results were predictable. Although the percentage of illiterates in the country fell from 20 percent to 17 percent between 1870 and 1880, the total number rose from 5.7 million to 6.2 million. They were concentrated in the South, which had 5 percent of the country’s illiterates. In the South as a whole, 37 percent of the population was illiterate, with a high of 54 percent in South Carolina. Much of this was a legacy of slavery, since the rate of illiteracy among black people was 75 percent.

The bill had support among Black Americans despite concessions made to Southern Whites which recognized segregation’s legal footing in those years. This was before the Supreme Court decision.

The bill wanted an altogether appropriation of $105 million dollars in support funds (matched by the states) for primary and secondary education systems. The spending structure was marketed as jumpstarting primary and secondary schooling in a way that would eventually not need federal assistance. The bill would pass the Republican-controlled Senate throughout the 1880s but, it was consistently rejected in a Democrat-led House of Representatives. Finally, the 1888 elections rolled around and Republicans received a trifecta.

Benjamin Harrison was voted into the White House (and supported the bill as a Senator) plus the Republicans controlled the House of Representatives and the Senate.

However, the Blair Education Bill still failed at the dawn of the 1890s.

Southern Democrats were experiencing the aforementioned economic boom and now argued they could fund their own schools. Also Republicans in the North had grown weary of continued efforts to enfranchise African Americans in a violently resistant South. Members either moved alliances to growing pro-business ties or pushed for immediate action on voting rights in the South - something that had little political currency.

The Reconstruction energy had fragmented and moved on.

The rise of the new southern economy and the tragedy of the Blair Education Bill (federal education funding would not happen for nearly a century) underscore the complex and unequal reality of this region.

A place still psychologically wounded by the devastation wrought during the American Civil War.

The South is central to American culture and the American experience. It is also one of the main centers of our diversity and our folk understandings of our nation. The American South is a story of authentic and real redemption. However, the dueling fates of economic exploitation and democratic/economic self-determination are constantly at a crossroads in this region.

Nevertheless, there can be more historic elections in the South going forward.

Brunswick, Georgia USA - January 2, 2021: Scenes from the drive-in rally for Georgia Senate candidate Rev. Raphael Warnock (Democrat). Courtesy of Shutterstock.