Shirley Chisholm’s Example

Empathy should be easy to achieve but is often difficult to execute, especially when we can find multiple reasons to withhold it—whether due to justified anger, personal hurt, or moral clarity.

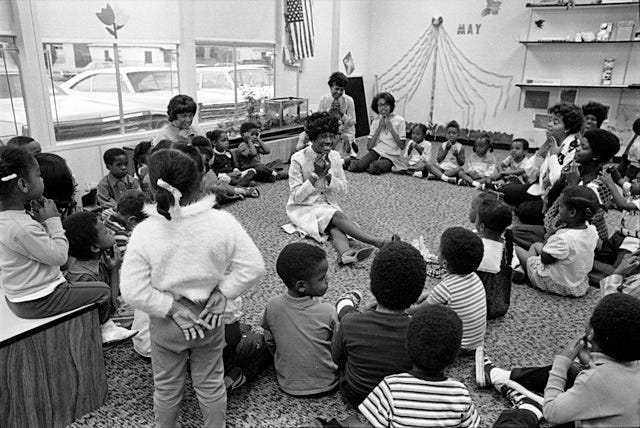

I often think of Shirley Chisholm, who famously visited segregationist George Wallace after he was shot. Chisholm was a trailblazing Black congresswoman, an outspoken advocate for the historically marginalized, and someone whose very existence challenged the racist power structures Wallace championed. Why, then, would she show him compassion?

Because she understood something fundamental: violence is always a terrible culmination of events. Whether it’s inflicted upon Black activists fighting for their civil rights or upon a conservative strongman clinging to a racist social order, violence corrodes our shared humanity. It is always wrong.

The Temptation of Schadenfreude

As the excesses of MAGA governance unravel in real time, many anti-MAGA circles are indulging in schadenfreude—reveling in the suffering of their political adversaries.

So, do Trump supporters deserve empathy?

I won’t extend empathy to those who knowingly voted for cruelty, those who cast their ballots to punish the outgroups they fear and resent. Yet, I also recognize that much of the mainstream media and centrist political class struggle to fully articulate what has driven Trumpism.

Some cling to focus group narratives that downplay how much of Trump’s appeal is about dominance, rather than policy.

Others rely on the outdated “economic anxiety” argument, avoiding a deeper interrogation of how that anxiety is racialized, weaponized, and deliberately misdirected.

But there’s an even bigger piece that remains unpacked—the role of right-wing media in hardening historic racial resentments.

For predominantly White, working-class Americans, their frustrations—their dissolved heyday, their shrinking communities, their economic decline—have been carefully framed not as a product of plutocratic greed or corporate extraction, but as the fault of immigrants and “uppity” minorities.

Centuries of social conditioning have primed people to react with hostility toward the unknown, even when the “unknown” is just a different shade of their own struggle.

So yes, some Trump supporters act in overtly prejudiced ways. Others operate from an implicit bias they don’t even recognize. But when they step into a Trump rally—a space designed to unleash grievance and rage—it “feels right” to them.

And it feels even more effortless when their entire geographic, economic, and media environment shields them from dissonance, from exposure, from ever having to question their worldview.

Attracted to Trumpism Like Moths to Light

Trumpism is, at its core, a marketing operation—one that packages White revanchism, rural exceptionalism, and performative masculinity into a digestible, consumer-ready product.

The pickup truck.

The rifles.

The camouflage aesthetic.

The “rugged individualism” mythos.

All of these are not just cultural signifiers—they are deliberate branding choices meant to evoke an America as the world’s last frontier. A nation of strong men fighting off “savages” to protect their families—not as foot soldiers of an exploitative institution, but as noble warriors of civilization.

A world where the factory floor wasn’t just an economic engine but a bastion of patriotism, where red-blooded, predominantly White Americans built the products that “won” wars and supplied goods to a backwards world.

The truth is far less flattering. America is more of a marketing invention than an idea.

Because even at its inception, America never truly lived up to the ideals it marketed. The slaveowners who drafted the country’s founding mythology were selling something they never intended to deliver. And yet, across generations, countless individuals of all races and backgrounds have fought tirelessly to make those ideals real.

But why is it so easy to roll back progress every other generation?

Because it’s easy to rile up populations who have been conditioned to see multicultural democracy as their enemy.

Trumpism operates as a distraction machine—a political circus designed to pull in voters through cultural grievance, feed them a steady diet of revanchist nostalgia, and then gut their economic well-being behind the scenes.

His campaign can roll into town, put up floodlights, posters, a stage, and Kid Rock, and turn a rally into a stadium event of collective rage.

And while the floodlights shine, his allies gut Medicaid, privatize Social Security, deregulate corporate oversight, and flood these very communities with opioids.

The small towns and deindustrialized regions that once served as America’s economic engine are now economic colonies, their labor extracted, their prosperity funneled upward, and their discontent weaponized against the very people trying to fight for them.

An Empathetic Conclusion

I don’t frame all this in a darkly clownish manner to engage in schadenfreude.

I say it because history is not a morality play—it is a cycle of conditioning, manipulation, and exploitation.

Shirley Chisholm’s example reminds us that we can still find humanity in those who have shown nothing but disrespect, dehumanization, and immaturity.

Because, at the end of the day, the fight for America has never been between Democrats and Republicans. It has always been between those who want to turn the country’s mythology into reality, and those who want to use that mythology as a smokescreen to maintain power.

Empathy is not about absolution—it is about understanding the systems that make people who they are.

And that understanding is what allows us to challenge those systems while refusing to lose our own humanity in the process.

Because, in the end, that is what pushes America beyond a mere marketing ploy and toward something real.

I am intolerant of intolerance, thus I lack empathy for those that lack empathy. I don't acknowledge the humanity of those whose behavior is inhuman, and I don't feel shame nor can I be shamed, because I never do that thing which would cause me shame. My motto is that of a doctor Do no harm.

This quality, or inability to empathize, conversely to empathize with your kin, is why we are alive today. It is a biological social survival mechanism.

When Jesus said "love your neighbor as yourself" he was talking in an era and time, when your neighbor was a kinsmen, probably related, went to the same temple, worshiped the same god, in he same place at the same time, had the same beliefs, rituals and traditions as you.

Very much different than what we in the 21st century consider a neighbor, who is simply a person who lives in your neighborhood, and with whom you may or may not have anything in common, other than race, religion, national identity if that.

If MLK Jr and Malcolm X lived next to each other or on the same block, would they be neighbors in the Jesus sense?.

How about a white MAGAt and a white progressive.?

A NAZI next to a liberal?

The ultimate question. If there was time travel, would you go back in time and kill Hitler.

Think twice on that one. If you did, you would never have been born.