One image branded into my psyche is a shelf full of video cassettes featuring the dazzling title artwork of numerous animated Disney films, which painted the spines of the cassette covers.

Pinocchio particularly frightened me as a child because of dark themes of hedonism and mischief, which led to tragically irreversible results. Pinocchio and the boys are led to a land called Pleasure Island with promises of no responsibilities but were instead transformed into donkeys (literal asses) after a night of parent-free shenanigans featuring billiards, cigars, and the scenery of Coney Island-style theme parks that Walt Disney disdained. (Urban carnivals at this time featured negative externalities that inspired Walt to create a more polished amusement park featuring his intellectual property - making it a theme park.) But also, as a young boy prone to falling into brainless traps, the lessons of Pinocchio were clear and relevant. The positive lessons regarding the evils of lying and the value of listening to one’s conscience are timeless and a reason why I love this film and property to this day. Cinderella and Bambi were also in this collection of animated films, along with the Many Adventures of Winnie the Pooh, Beauty and the Beast, and a hollow box for The Little Mermaid (as a younger version of myself broke the cassette to my sister’s chagrin due to it being her favorite Disney animated feature in the ‘90s and 2000s).

Growing up I was lucky to go to Disney World in Florida twice (once was a classic midnight surprise announcement) and I also was an avid fan of the Disney Channel well into my adolescence. The cultural reach of Walt Disney Studios can’t be understated as generations of Mickey Mouse ears have proliferated America (and the world) since the dark days of the Great Depression. As a personal (and cathartic) exercise, I have been watching almost the entirety of the Disney pantheon, at least in terms of theatrical entertainment. Though, I did watch some of the made-for-TV productions that lit up early televisions in the 1950s and 1960s.

Currently, I am at The Jungle Book in 1967.

I like to think of Disney history in distinct periods:

Oswald and Mickey (1923 - 1937)

The Disney Golden Age (1937 - 1941)

American Patriotism and the Disney Brand (1942 - 1949)

The Rise of a Family Entertainment Juggernaut (1950 - 1967)

The post-Walt Loll (1968 - 1983)

The Eisner Period (1983 - 2003)

The Family Entertainment and Vacation Empire (2003 - present)

With this delineation, I am entering the fifth era.

This deep dive has been fantastic. I reflect on the massive artistic contributions that highlight our dreams in the form of animation while also experiencing a subset of primary sources tracking the long transformation of the film industry, America’s soft power, and family entertainment. Still, it is also cringe-worthy when I receive a firsthand look at the dark stereotypes surrounding minority-based roles, the blatant absence of agency for many women, and the cultural pressures pushed upon males to use violence as a way out of their problems (this was waning by the 1960s). But, as an example, the conclusion of the live action film, The Light in the Forest (1957), is the romanticization of a fist fight in the middle of a colonial American village where the locals cheer on the two male characters. The film also states that Native Americans can’t fist fight which was also really hard to watch because it just made zero sense but was rife with racism. Also, the utilization of violence is an age-old cultural pressure continuously perpetuated onto boys and men, despite humanistic advancements in cross-cultural, interpersonal communication, as well as diplomacy and emotional intelligence.

As the nation’s people evolve, so does the nation’s premiere entertainment company.

To avoid being raided during the post-Walt era, the company expanded from a large family-run studio and technology development enterprise into a globally diversified conglomerate with sophisticated market interest due to a variety of product offerings (including cruise lines and hotel chains).

This evolution also parallels social development.

My mother’s favorite animated studio film is Mulan. She liked that my sister’s favorite princess was originally Bell due to her love of books, but we were in theater seats as soon as a Disney film was released about a woman’s fight to preserve for father’s honor and life by undoing the traditional assumptions of misogynistic structures. Mulan turns the Disney princess trope on its head. For one, Mulan’s mother and father are both present and deeply influence her worldview. Secondly, once the imperial government calls for men of all ages to fight invading Huns, Mulan takes her father’s sword and armor and pretends to be a young male. Not only does Mulan display intense agency and tenacity, but she is also the key driver of the film’s plot (and her own success) as her decisions and her influence on supporting characters allow for victory.

Mulan suits up:

Mulan is easily in my top five favorite Disney films that came out of the flagship animated studio. It wouldn’t be until later in life when my eyes were opened further to the ways masculinity can be harmful and I grew a deeper appreciation for the cultural signals passed onto a younger me that were also facilitated by my mother. Simply put, my male-centered cultural memory was benefited from the depiction of a Disney princess that is in control of her own destiny. Young people today deserve that same exposure, no matter what a vocal and intolerant portion of the nation declares.

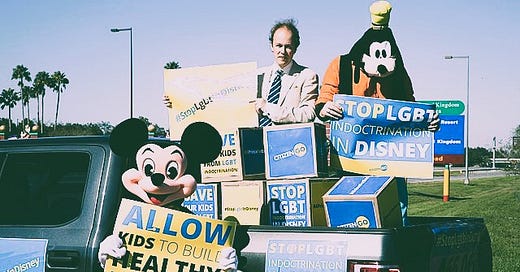

I reflect on this because the Republican party and the American right-wing have decided that Millennials and Generation Z have had bad curriculums and bad cultural pressures that (God forbid) make them consider the lapses in human rights towards marginalized people as they exist in an autopiloted, structural manner.

But the problem is not Disney.

The problem is a revanchist offshoot of conservatism that is inheriting a world where their cultural assumptions of otherized groups have been unwound in the face of actual reality. Instead of looking inward, this political movement (which is enough people to reach critical mass and influence a major political party) has lashed out at real education and at powerful pushes for multicultural representation. The American right wing does this without considering the experiences and feelings of marginalized people, who either lived in a time when they were forced to the sidelines or have to live with people screaming “critical race theory” at them when simply reciting their ancestor’s lived, journaled, and hueristic experiences.

Disney is just fine and the fact they want to include gay characters is more than fine. It’s purely American.

The Republican party’s deep-seated blind spots and the revanchist evolution of many parts of the larger conservative enterprise are the reason youth voters sway leftward. This movement’s worst aspects trickled down into the new century and in some of the younger conservatives. Thus, the larger philosophical school is used as a launder for racism, hatred of women’s autonomy, non-Western religions, and melanated immigrants.

That’s a Republican problem and, really, more of a kitchen table issue about what parents tell their kids about their society and the people that don’t look like them.

It’s ironic the conservatives aren’t strongly considering this last point.