April 6, 1917: “We are provincials no longer.”

Upon Congressional approval, the United States declares war on Germany and enters World War I.

April 6 marks the culmination of months of international headwinds pushing a neutral United States into the European conflict known to contemporary audiences as World War I.

After the German government introduced a policy of unrestricted submarine warfare in January, a form of battle that had been killing Americans since 1915, United States President Woodrow Wilson was weary about the prospects of continued neutrality. Wilson coined “America First” and used the slogan, “He kept us out of war” in his presidential campaign. But now he was drawn into a European war and feared ending the over-a-century-long Neutrality Proclamation, beginning under President George Washington.

Weeks later, revelations were made public of German leadership’s intention to promise Mexico the lands of Texas, New Mexico, and Arizona, as well as financial support, in exchange for an alliance against the United States. Wilson had already ended diplomatic relations with the central European country and now he had a public outcry to navigate as the Zimmerman telegram hit newspapers in March.

In Wilson’s second inaugural address, he displayed his high-minded sentiments:

“We are a composite and cosmopolitan people. We are of the blood of all the nations that are at war. The currents of our thoughts as well as the currents of our trade run quick at all seasons back and forth between us and them. The war inevitably set its mark from the first alike upon our minds, our industries, our commerce, our politics and our social action. To be indifferent to it, or independent of it, was out of the question.”

However, it is this next part (later in the speech) that articulates the new era Americans had entered:

“We are provincials no longer. The tragic events of the thirty months of vital turmoil through which we have just passed have made us citizens of the world. There can be no turning back. Our own fortunes as a nation are involved whether we would have it so or not.”

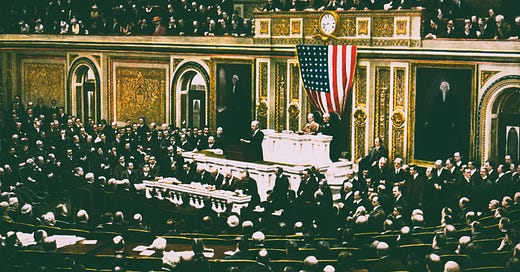

It wouldn’t be long after when Wilson convenes and addresses a special joint session of the national legislature for a declaration of war on April 2, 1917. The speech was received successfully, and it took four days to mobilize a constitutional declaration of war within the Houses of Congress. The U.S. was preparing a military draft of 500,000 soldiers and mobilizing the necessary resources for war.

“We have no quarrel with the German people. We have no feeling towards them but one of sympathy and friendship. It was not upon their impulse that their government acted in entering this war. It was not with their previous knowledge or approval. It was a war determined upon as wars used to be determined upon in the old, unhappy days when peoples were nowhere consulted by their rulers and wars were provoked and waged in the interest of dynasties or of little groups of ambitious men who were accustomed to use their fellow men as pawns and tools.”

The revolution in Russia aided Wilson in framing the effort as one of democratic nations. This is crucial to U.S. foreign policy as it changes from isolation and neutrality to intervention in neighboring affairs to all-out global interventionism. America’s outfit as a resource-laden nation with democratic ideals embedded in its genes means that it has an outsized ability to influence global political trends.

As Wilson muses to Congress:

“A steadfast concert for peace can never be maintained except by a partnership of democratic nations. No autocratic government could be trusted to keep faith within it or observe its covenants. It must be a league of honor, a partnership of opinion. Intrigue would eat its vitals away; the plottings of inner circles who could plan what they would and render account to no one would be a corruption seated at its very heart. Only free peonies can hold their purpose and their honor steady to a common end and prefer the interests of mankind to any narrow interest of their own.”

World War I also accelerated democracy and representation on the home front.

In contemporary memory, the United States has never been an isolationist nation. There have been calls for isolationism on both sides. However, it has never garnered enough political currency to transform those calls into a streamlined agenda in Washington and in state capitals. I would argue that isolationism is different from calls to end engagements that have been proven failures. It is possible to both believe in America’s role in the world as a shining democratic light and also raise concerns over negative outcomes.

Still, there have been voices that have used Putin’s rhetoric to justify the invasion of Ukraine in order to cripple Americans’ view of the war crimes and demagogue a popular sense that our leaders in Washington don’t focus enough on their home districts. J.D. Vance infamously said he didn’t care about what happened in Ukraine on the campaign trail and recently appeared on Tucker Carlson’s show.

Ohio Senator J.D. Vance arguing the U.S is spending too much money to “the most corrupt country on the face of the planet” as it is getting invaded by its neighbor, a former superpower and much larger entity.

This Fox-sponsored host is known for using Putin’s own talking points:

It’s important to assess America’s principles and democracy as part of a larger ecosystem of global affairs. It is the best way to come up with prudent conclusions backed up by the best available information. Vladimir Putin’s invasion of Ukraine is a gross violation of human and international rights. The Ukrainians are engaged in a worthy effort to protect their home. No matter how many conspiracies form or selfish arguments are made against Ukraine, this won’t change. It is honorable to watch people protect their civic life amid devastating conditions. However, it is also uplifting to see the positive sides of American internationalism reflected in the aspirations of a smaller nation fighting for identity and sovereignty against a bigger nation.

This nation is as much an ideal as it is a federation of states, a national identity, and a cultural symbol.

Some people utilize the imagery, history, and aesthetic of America to impose a selfish agenda. However, it is possible to pay attention to the problems miring Americans at home while also acknowledging our importance to the rest of the world and how those two spheres intersect.

Actually, the situation with "unrestricted submarine warfare" was that the German decision in 1915 to execute unrestricted submarine warfare had resulted in the sinking of the Lustania, with several hundred Americans aboard being lost; this brought the first surge of war fever here and almost resulted in a US declaration of war. In the face of that, the Germans pulled back and stopped the policy. Then, in early 1917, in the face of battlefield reversals and the effectiveness of the Allied blockade of Germany, unrestricted submarine warfare was again adopted and it came close to bringing Britain to her knees that spring. The sinking of three American ships was used as the reason to declare war 106 years ago today. With the US Navy adding to the Royal Navy and the institution of a convoy system, the submarine threat was blocked by the end of the summer.

But Americans had not been lost between the sinking of the Lusitania in May 1915 and February 1917 when the campaign began again.

Interestingly, the German defense about the Lusitania was that it was carrying war cargo in addition to passengers, making it a legitimate target. The British of course denied that. However, researchers in the 1990s found information in the British records that the ship was carrying a big load of rifles and ammunition to the British Army, hiding the fact by using a passenger ship. Also, the Lusitania was found where she went down off southwestern Ireland, and the presence of the military shipment was confirmed.